Itself

Itself: Guidelines

Russian-language print versions of Apraksin Blues are available upon request.

Price per issue $15 (check or cash; price includes domestic or international postage).

Apraksin Blues considers manuscripts in any format — preferably literate — proposals and wishes in any form. We request that submissions be limited to previously unpublished texts.

Apraksin Blues accepts inquiries regarding custom literary translation and editing of Russian and English literary texts.

Apraksin Blues welcomes volunteers. For information on getting involved, contact any of our editorial addresses.

Our Partners

**HOT ISSUE**

AB №35 – If…

**HOT ISSUE**

AB №35 – If…

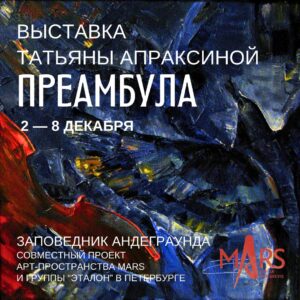

* If It Is the Reason (Blues Mondo). T. Apraksina

“nothing hatches without a nudge from doubts”

* Petals of Meaning. B. Solozhenkin

“All this, that was and will be, simply ‘Is'”

“From below you can’t see the top, the rough ear hears only ‘Moo-oo-oo’ in Mozart’s melismas”

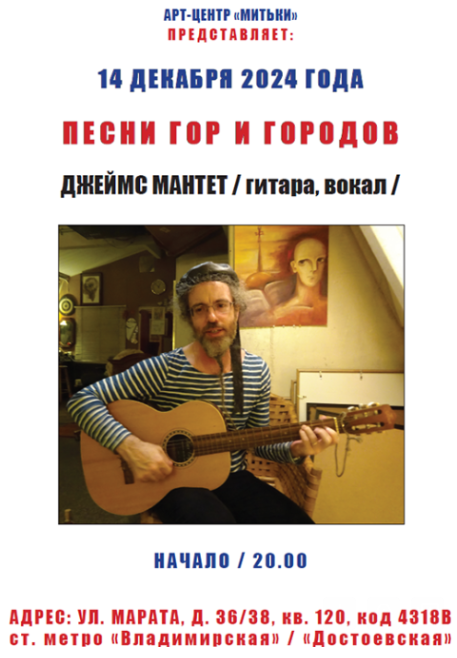

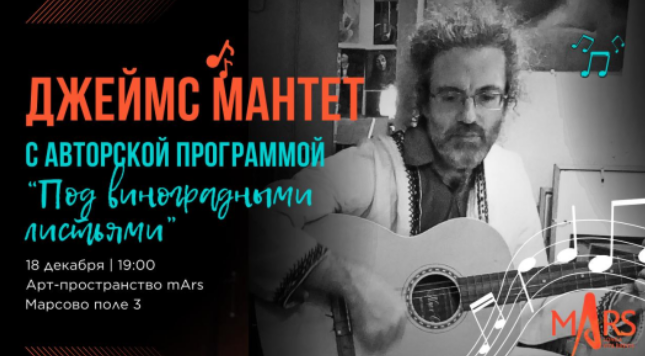

* The Labyrinth of Mormon Trails (Blues Report). J. Manteith

“The desolate expanses of the American desert now seem filled with presence”

* Josephus Flavius: The Paradox of a Modern Hero. E. Molochkovetskaya

“The main paradox of the image of Flavius lies in his absolute modernity”

* Citizens of Nevsky. N. Mazurenko (review)

“Cemeteries, churches, boutiques, restaurants, prostitutes, swindlers, nouveau riche, theaters, galleries, courtyards and backstreets — the author’s gaze has penetrated everywhere”

* The Creative Will (continued). W.H. Wright

“Great artists are never a product of the public spirit”

* Decembrists Street’s Circular Breathing. O. Romanova

“I really want us to become famous.”

* The Love Story of a Potato. P. Gripari (translated by L. Efimov)

“How elegant you are. Just like a frying pan.”

“I want to marry your potato”

* Where to Look for Enlightenment… I. Dudina (review)

“…a philosopher, a writer, maybe even a prophet awoke in him”

* Lessons of Vicissitudes. Lama Karmapa (translated by V. Ragimov)

“Everything that exists is just cycles of the fruits of the imagination”

“A Buddhist is not necessarily a cook, but someone who loves interesting food”

* Chasing the Wind. E. Molochkovetskaya

“Like any normal alchemist, he begins with internal transmutation”

* Spiritualism in the Literature and Philosophy of Restoration England. V. Trofimova

“The English freethinker became a ‘co-author’ of the Russian writer’s spiritualist novels”

Polemics Session: “The Space of Genuine Art”: Rethinking the Aesthetics of Huntington Wright.

“It would be good for musicians not to rush to exchange their tailcoats for T-shirts”

***

The Age of Blues

November 29, 2025, St. Petersburg. Read the issue.

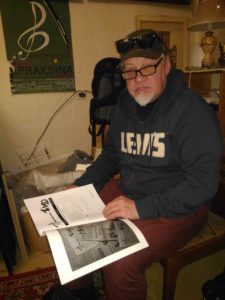

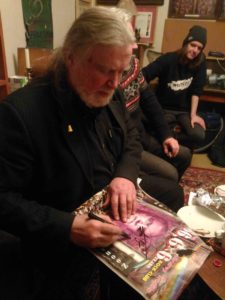

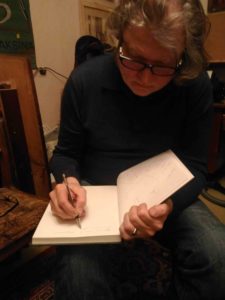

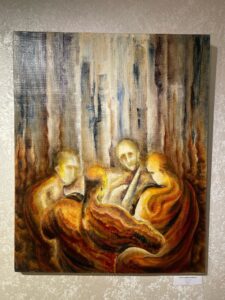

Photos by Natasha Vasilyeva-Hall:

Photos by Olga ...

+

AB issue 34 — In Worlds and Times — see it here

* Self-Portrait as a Method of Blues: In ...

+

AB issue 33 - Transcription of Multitudes - see it here

* Tower (Blues Mondo). Tatyana Apraksina

“from the objectlessness of ...

+

AB issue 32 - see it here

* The Place of Measure (Blues Mondo). T. Apraksina

* Great and Mighty. What ...

+

AB 31, our first issue since 1998 to be produced and published entirely in St. Petersburg, is imbued with the ...

+

The Apraksin Blues editorial board is pleased to announce the long-awaited publication of AB №30, "On the Way." Authors and ...

+

+

All-All-All!

Authors, readers, admirers, past and future! And just good smart people!

To everyone who knows us, who know each other, ...

+

+

***

Its BILLBOARD

for gourmets

Translations Department

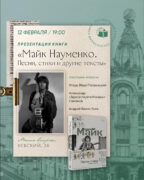

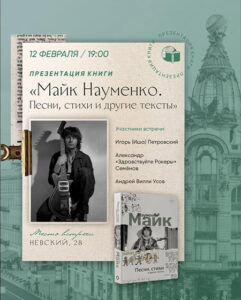

- Echoes of Influence: New Edition of Mike’s Texts Includes Translations of His Songs

January 18, 2025

Echoes of Influence: New Edition of Mike’s Texts Includes Translations of His Songs I’m excited to share some great translation news from late 2024, carrying over into early 2025: the major Moscow publishing house AST has released a new book in the ser…

Read more - Highlights of 2023 in the AB Translation Department

January 7, 2024

The past year has given many reasons for gratitude and hope in various areas of the Apraksin Blues Translation Department’s engagement with literature and literary translation. Some events I’m pleased to share word of include: – Taking part in publishi…

Read more - The Encyclopedia of “Sweet N”

December 19, 2021

The Encyclopedia of “Sweet N”: James Manteith’s presentation from the 50th International Scholarly Conference of the V.I. Startsev International Association of Historical Psychology — Historical and Psychological Aspects of the Fall of the Soviet Union…

Read more - In Support of Evolution: Boogie-Woogie Thinking

November 24, 2021

Back in St. Petersburg by the beginning of November 2021, AB’s editors immediately found many opportunities to assess current attitudes toward culture. At the 5th Cultural Congress, in which we took part, we encountered the opinion that the era of the…

Read more - Summer Report: Love and Attentiveness

June 22, 2021

Summer has arrived. According to Far Eastern traditions, it’s now a horse month, during which the sages advise to take special care to curb all manifestations of power now faced by and available to many. Our authors continue to work or rest as b…

Read more - Robert Monteith: A Knight for Peace

May 27, 2021

(English translation of a May 17 lecture for the International Association of Historical Psychology conference “Societal Atmosphere on the Eve of the Wars of the 19th and 20th Centuries: Historical and Psychological Aspects”) — James Manteith (A…

Read more - Long Echoes of Contrarian Crusades

May 27, 2021

Presenting on Peacemaker Robert Monteith in St. Petersburg via California — James Manteith (Apraksin Blues, Mundus Artium Press) In the wee hours of one morning in May 2021, it was my privilege to have a chance to give a remote Russian-la…

Read more - How AB met the New Year in St. Petersburg for the first time in 22 years

January 19, 2021

There’s no tree to be found, only fake ones or bunched branches. But just before New Year’s, a man appears on Garden Street with beautiful real trees brought from the Volosov region. The Haymarket tree fair at is closed due to the pandemic. AB c…

Read more - Voices in the Petersburg Desert

December 18, 2020

For obvious reasons, many have voiced surprise that we, AB editors, decided to make an attempt to come to St. Petersburg in 2020. We were also surprised, and even more surprised it’s happened. We already had enough challenges in 2020: in addition to ou…

Read more - Arrival!

November 23, 2020

AB’s editor-in-chief and translation editor will be in St. Petersburg through early 2021. The phone number of the St. Petersburg editorial office is as before: +7 (812) 310-96-40. The Editors apraksinblues@gmail.com

Read more - Distance Learning

July 4, 2020

Now, with the release of Apraksin Blues №30, “On the Way,” another crucial phase begins — the stage of readers’ time with the issue, authors’ mindfulness toward each other, and discussion of what it’s all about. For the AB Translations Department, ther…

Read more - A beautiful chord: AB in St. Petersburg plays on

December 14, 2019

What might be said about the time spent by AB’s editors in St. Petersburg after the presentation of issue 29? Perhaps that it was a time of deepening relationships, joint initiatives and expectations. Let’s review some aspects of this deepening. First,…

Read more - Rapid development for AB’s physical existence in St. Petersburg

November 13, 2019

Events of recent days hint at a new cycle of development. AB has again made the crossing from California to St. Petersburg. Less than a day after arrival, Tatyana Apraksina managed to reopen a space and sit down to work at her desk in the magazine’s hi…

Read more - “Freedom” declared in Petersburg

November 2, 2019

by contributing translation editor James Manteith Photo: Irina Serpuchyonok Just a few days remain until the planned presentation, in St. Petersburg, of the latest issue of Apraksin Blues, №29, “The Career of Freedom.” As in 2015, for the presentation…

Read more - Preparing for St. Petersburg

October 31, 2019

What needs translation, in this case and maybe always, is reality.

Read more