Deserts and Fields of Timeliness (Blues report)

Published in: 16. Family and SlaveryOn January 16, 2009, the world lost one of its great artists — if a great artist can be lost, and if he belongs to the world enough for it to lose him. Andrew Wyeth was a major artist. Talent and tenacity enabled him to stand apart from both realism and reality as defined by his discipline’s contemporary authorities, those guided by cues remote from artistic purposes. His love, his concern, he said, was for portraying “strong-willed people,” predominantly those who preferred, like him, to live in isolation.

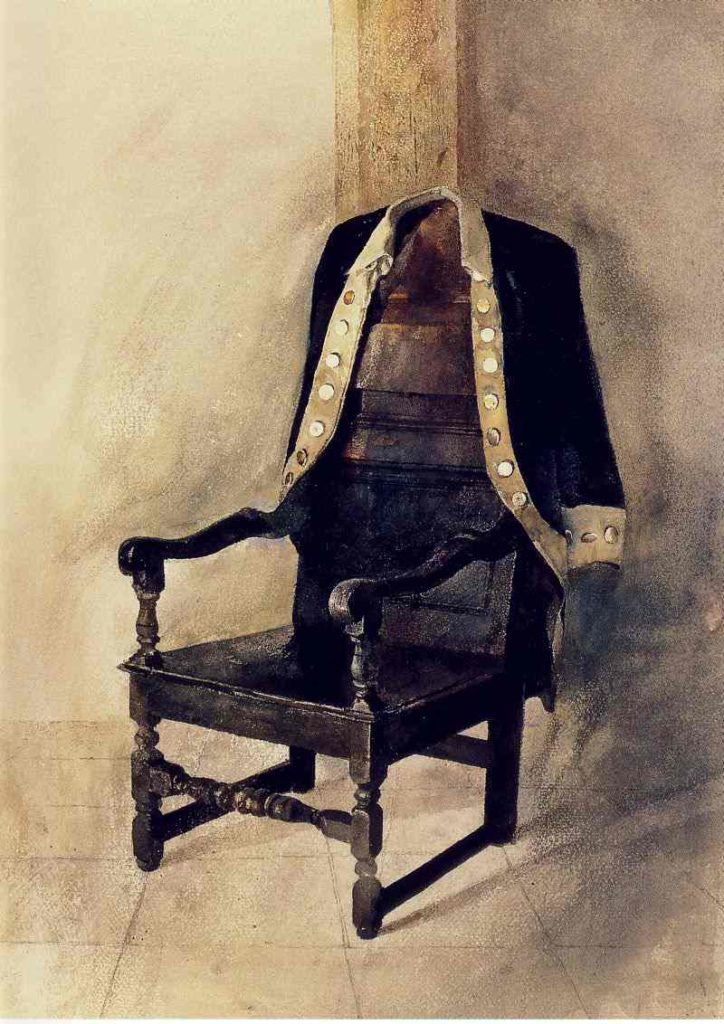

Andrew Wyeth. The General’s Chair. 1969

Canvas after canvas shows values that, for much of the artist’s lifetime, found more admiration among amateurs than among the specialists of modern aesthetics. That lifetime over, as Auden wrote (on the death of Yeats), “he became his admirers.” To some, Wyeth’s paintings may have seemed too specifically material, superannuated in sensibility, to seriously interest those with the experience and daring to seek cultural investments more attuned to transient notions of future lucre. His art’s sophistication had no connection with technology, with progress, the driving forces of civilization’s ascents and collapses.

Creating his paintings — spare and yet meticulous, unhurriedly detailed (and yet reportedly numbering in the thousands) — Wyeth outlasted, both in years and relevance, countless contemporaries and many later contenders. His lifetime’s placement recalls Thomas Hardy, who preserved the tie he’d forged with the nineteenth century in the twentieth century as well. Or, more recently, Solzhenitsyn, faithful to his creative and moral principles in each of the two centuries framing his life.

There is a heroism all artists possess in one degree or another. By creating, by not restricting themselves to roles as observers, they declare their opposition to a morality of utility, in which the commonplace exists for rational relationships. Artists have means to assert the beauty of the thing in itself, of unmediated human response.

In an artist of Andrew Wyeth’s caliber, this heroism approaches the absolute, with the line between the well-made painting and the life of the well-made subject dissolved entirely. Hemingway may have had a similar understanding of craft, deftly depicting examples of human skill, of humans shaped and worn by the power of their own preferences, in matters of directions chosen as desirable. He and Wyeth, attaining artistic maturity in periods of historical turmoil, also similarly chose to respond with a cleansing of vision, abstaining from clumsy new myth-making (the seeds of Disneyland were planted on America’s West Coast while Wyeth painted in the East).

Civilization’s flower opens, opens, opens, and out comes death, the end, innovation’s hidden offspring (the fall of Babylon, crash and crisis, the post-Babylonian spirit evoked so powerfully by writers like F.S. Fitzgerald). “Why innovate? Why know the present time, why adapt to it?” Wyeth’s paintings seem to ask. While the artist’s heart is alive, it holds deep resources for all times, and art runs no risk of failing to reveal new possibilities.

Andrew Wyeth. Christina’s World. 1948

Andrew Wyeth passed away at 91 — a seemingly Biblical lifespan, in years multiplied by a factor of dignity. His departure may leave less sorrow than shame, I think, at all the pettiness paid tribute in that time. He lived longer than many had realized, and his works may live longer yet, if the timely still yields to the ageless.

Speak Your Mind