“China’s a Great Big Country!”

Published in: 29. The Career of FreedomWhy is this old Russian song about China so likable? I, at least, liked it right away… And I doubt that my penchant for it will ever fade. What makes this song so powerful and unique?

The first line, which serves as both a title for the song and a refrain for three of its four verses, even seems flagrantly dumb, almost a tautology, a provocation. But if it is so obvious that China is a big country, then why are there so few famous songs about it in languages other than Chinese? In a world evidently short on such songs, it’s somewhat surprising that “China’s a Great Big Country” exists at all. In any non-Chinese language. It doesn’t matter that China is Russia’s neighbor. For ages, the two countries and peoples have had many common interests, ties and opportunities to notice each other. Maybe some similarly themed songs have been written in Russian, whether by inspiration or on commission. Maybe there are many fine Chinese songs about Russia. But this Russian song about China has turned out to be truly wonderful. It has lived a long, rich life. That takes a special alchemy of conditions.

There are many versions of the lyrics for “China’s a Great Big Country.” The version I love most, to which I remain faithful and will refer to here, I first heard in the big country of America. A capella. Oddly enough, the song was spontaneously reconstructed from memory by a Russian poet who learned it in the mid-sixties. The poet herself first heard the song, along with other semi-marginal material, while accompanying a Lenconcert performer on tour in Moscow. Late one night, that performer and a forensic doctor, both of them song aficionados, informally swapped repertoires. The performer and doctor sang about urgent matters, but cheerfully and without histrionics. This mutually enriched them. As a result of that evening, which followed a common pattern of musical exchanges, the poet was also enriched. Later, I was, too.

Recently, briefly in Hollywood on business, I realized I didn’t want to go out on the first night. Instead, I wanted to sit in the motel room with a guitar and “bash out” “China’s a Great Big Country,” as the song itself puts it. Well, not merely bash out the song, but also ponder its mysterious power, its anatomy and spirit. And then refine the translation. The translation of such a marvelous song should, of course, inhabit the original melody for an authentic singing experience. This Russian “China” readily crosses cultural and linguistic borders, further proving the song’s durability.

… Plantations are there all over.

They raise aromatic tea,

Everywhere gardens flower.

Generally speaking, songs tend to arise and exist most fully in the context of specific peoples. Exoticism can seem strained. Internationalism is an elusive ideal. Yes, there are many translations of Chinese poetry into Russian, as well as into many other world languages. In general, there is a large Chinese contingent among many world cultures — not to mention the standard industrial level adapted to China’s global material needs. But somehow, such cross-pollination has engendered relatively little inspiration to sing about China itself. Admiration for China tends to be rarefied, speculative… Such qualities do not necessarily yield good songs or even any songs at all. Exotic lyrics in a compelling song, as a rule, channel pure imagination — as in the Beatles’ “Octopus’s Garden” — or stay lightweight — as in Cole Porter’s “I Love Paris.” Some worldwide hits use imaginative material based on historical subjects — “Brown Sugar” by The Rolling Stones, say, or “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” by The Band. Yet China is not only real and wholly non-invented. It is complex, huge, important, and physically, historically and psychologically distant from the West. The phenomena of colonialism and rapprochement formed only conditional, shaky, inconstant ties. It is perhaps harder for a non-Chinese to establish a close relationship with China than for a non-Frenchman with Paris. For the best songs to arise, the author has to have a direct, personal relationship with the material. It seems that namely Chinese people have the purest direct tie with China. Outside China, in the best cases, China is approached either from a respectful distance or with a keen research interest — which also helps reveal the essence of one country to a resident of another. But a good non-Chinese song about China is even rarer than a good non-Chinese study about China.

The song “China’s a Great Big Country” has existed for decades and still gives an impression of unsurpassed freshness and relevance, of a kind of primacy. It deserves international recognition as a masterpiece!

Everywhere groves of bananas,

White rice that smells so sweet.

Over there creep lianas, Alyokha!

Over there flowers maize…

“China’s a Great Big Country” reveals a lively sung view of China itself. The view’s authenticity is somehow palpable. What convinces, in part, is the motley everyday language, a vessel for dollops of exotic material. The song’s hero needs no sinology. He does not think deeply, does not acclimate to China. He invents nothing — no imagination is needed. He understands that the simplest observations may serve as the most profound introduction to the real China — anything more would be overkill, not an introduction but a self-proclaimed, hollow master class, a different kind of sacrilege than gross fabrication. In any case, China is such a big country that its scale is best conveyed by the fact that even a person from such a big country as Russia prefers to stick to simple observations, almost primitive clichés. The hero simply describes those impressions he considers appropriate to put in words. He is a man of few words… But a series of unforgettable miniatures somehow shines forth in the morass of stock phrases. Clichés ennobled with real poetry cease to be clichés. Laconicism turns into a standard of reliability — as if the hero knows the big country can say more for itself than he might ever wish to say of it. Great big China can do anything…

Down a blue river’s bends

Junks in the mist have vanished.

Poor simple fishermen,

Yellowy like bananas…

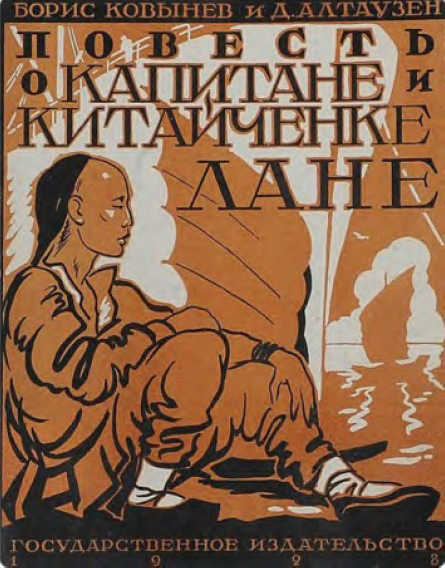

I. Rerberg. Illustration for “The Tale of the Captain and the Chinese Boy Lan,” 1928

In the song, a strong impression of China scarcely indicates the hero’s desire to become Chinese. The hero does not stand on ceremony with China, does not try to be objective — which says more about him than about China, and allows the listener to make the necessary perceptual adjustments. Especially in the song’s final couplets, the hero makes it clear that for him, Chinese life would remain foreign. Certain features of the cuisine, more extreme than sweet-smelling white rice, prove the last straw, “no grub for us Russians.” Fair enough. Why wander too far on someone else’s turf? All the same, it will lead nowhere, and it’s hard to feel up for that anyway… But foreignness doesn’t make the hero lose interest in China. His business is not to love China but to sing and convey precisely the scale of Chinese phenomena, to sing China both an ode and a blues. China is too big a country, too intriguing ever to warrant forgetting.

…[They] spread out their watery nets

All down the riverside…

Junks are their apartments, Alyokha,

And where they go to die.

The song’s words and images repeat. As a colloquial conversation, as a narrative and, it would seem, as a hodgepodge with little artistic merit. But in literature — especially in song — repetition may enhance artistry by establishing motifs. The song’s repetitions help reveal its internal structure and implications. Here, repetitions cast a spell.

O China’s a great big country.

Plantations there past all number.

Shanghai is a huge port city

That sits right beside the water.

The unity of the song “China” is forged from “plantations”, “bananas” and, of course, “aromatic tea”… from a ubiquitous flowering and growth of sometimes lucrative vegetation… from “junks” and “Shanghai”… and, of course, from “Alyokha,” whose trusted place is free for any listener. The persistent, moderately pushy and obsessive repetition of certain words facilitates apprehension of the rest of the song’s content and lets non-repeating, sometimes showy or slangy words to stand out even more, as the author’s special finds: say, “lianas,” “maize,” “gangs,” and, as a last-verse apotheosis, “promenade,” “bash out,” “trepak,” “grub,” etc.

The same can be said about the simplicity of the structure of phrases, redolent of a desire for accuracy in conveying facts. The song’s restrained lyrical permutations breathe romanticism and enable better discernment of the hero’s true motives. He does not squander himself on cheap poetry but is quite the poet when his theme requires such means. A sense of proportion is also a necessary qualification for a poet. And one senses that the hero is among those blessedly born poets and never weaned away from poetry by life. On the contrary: knowing the severity of life, perhaps in a range of countries besides great big China, he knows that singing has to come from the heart. Whether about human fates or about any of the world’s ten thousand things. Fates and things, things and fates — they coincide exactly, they are equal. Ask the poor fishermen. Ask the ships transporting great big China’s tea.

Shanghai meets the incoming fleets

That sail from the sea in gangs

To haul aromatic tea, Alyokha,

Right back the way they came!

Tea turns out to be the whole song’s locus — it appears in three of the four verses. The tea sung of is not called “rare.” Simply being “aromatic” already lends it a sturdy figurative definition, sufficiently evocative of the reverence it commands from the song’s hero. This tea may be of some very typical sort and quality or may span more sophisticated blends. But it seems that neither the hero, nor Alyokha considers subtleties the foremost thing about tea. They are not spoiled aesthetes. Tea is a reassuringly familiar phenomenon, compared to the song’s rather alarming evocations of shark fins and worm soup. The hero’s interest is excited enough by the simple fact of an aroma and, moreover, by the penchant for tea among the masters of plantations and ships, among the Chinese themselves and all those to whom the ships haul wares. Clearly, this is a case of heavy local and international tea expenditures. Maybe the hero wants to team up with Alyokha on capturing some of the alluring market. Maybe this dream is set to come true in the near future. Or maybe at some distant time, or maybe never at all. Maybe the hero and Alyokha themselves are in China at the moment of the song’s nascence. Or maybe circumstances have flung them onto a fringe where thoughts of access to a cup of tea or even boiling water already verge on the fantastic. You, the listener, don’t know, which also enhances the song’s air of mystery, the feeling of eavesdropping on someone else’s secret conversation, who knows where, in some dark place where you might accidentally be mistaken for “Alyokha.”

O China’s a great big country.

The Chinamen promenade,

Drink aromatic tea,

Bash out their Chinese songs…

The song’s language helps to better gauge the personality of its narrator, the eyewitness to China. As the song progresses, his state of mind seems increasingly limited, pleasantly enough. In the song, mental limits do not equate to blindness. On the contrary, they serve to concentrate narrative and musical movement.

The melody gives a special, impressive flavor to the repetitions in the verses, yielding a heightened experience of the song’s twists and turns. The verses and melodic structure brilliantly follow the rhetorical requirements of the lyric epic. Each verse features a well-delineated opening statement, a development of action, a climax, a denouement. The same observation can be made about the verses’ relationship to each other. The song has absolutely no superfluous moments. On the contrary, instead of linguistic polish, more often the melody plays a decisive role in the transmission of verbal nuances, making it possible to understand the hero perfectly. Repetitions of the unstable note B in the third line of each verse build up tension, quicken the pulse. When at the end of these lines the melody descends by a tone and semitone, the listener already realizes that the song is relaying something extraordinary, with hidden inner content. It is immediately clear that “tea” at the end of the third line falls into such a special category. In the same position and with the same pithy load are both “fishermen” and “Shanghai,” and again “tea” — these fundamental images will receive the song’s most profound development. And the melody culminates in the sixth line of each verse. There, “rice” resounds with at a hitherto unimaginable pitch of drama. “Riverside” expands majestically. Ships arrive, and their procession passes vividly in the mind’s eye. And “trepak” dances like circling sharks and as a quite convincing, satisfactory version of the lyrics, whatever other alternatives may exist. It’s a good description of a weird Chinese dish! Finally, the denouements — “maize,” “go to die,” “back the way they came” — ebb away into silent musings between the verses, right down to the last kiss-off with which the song ends.

Not long ago, I learned that the song’s lyrics have a source in the prelude to a 1920s work by the Soviet poet Jack Altausen. Most likely, few of those who have sung and loved this song — especially in the version that I love the most — have suspected this origin or, knowing about it, attached any special importance to it. In childhood, Altausen lived and worked in China, including in Shanghai. This pedigree, perhaps, partly explains the lyrics’ vestiges of authenticity and professional craftsmanship. But Altausen’s original has a number of differences from the song “China’s a Great Big Country.” A song directly superimposed on Altausen’s text could hardly have become such a hit, such an obvious masterpiece. The Soviet poet wrote not a song but a poem about a Chinese boy named Lan. Tracing a specific personality and plot, along with a more traditionally expressed sympathy for a people oppressed by imperialists, the poem showcases the author’s talent and subtlety: “The ships slip away in the mist, / They melt / Like the moonlight’s glint, / And the Chinese boy Lan / Looks on as each one vanishes” — but leaves the material less flexible and portable than it, thank God, would become. Besides, Altausen has no Alyokha! Yes, his song lacks Alyokha and much else that anonymous evolution would provide. Namely folk craft spun the wheels to create an unquestionable hit. It seems that Altausen, who died in the Great Patriotic War, would be glad about his poem’s fate. Although largely unknown, he remains the author of much of the wonderful poetry preserved in the song. And so many people have entered into co-authorship and empathy with him! The song “China’s a Great Big Country” is a crucible of times and circumstances that exceed the personality and intentions of one individual author. This “China” has served time in Magadan. It has served its full sentence, it has escaped from there, it has never left at all. Perhaps this “China” would fit in just as well in Alcatraz or Soledad. Countless city apartments and train platforms have managed to be this “China.” “Tea” can also be an emblem for a host of enterprises, from the noblest to the basest — yet always very tempting! The “Chinese” can also be a panoply of inscrutable characters, who determine the choice of music, food and everything else in various conditions, which may be alien yet still spark curiosity. In Moscow as well as in Hollywood.

When it comes to the words “bash out their Chinese songs,” you involuntarily think — all the more so if you yourself are singing “China’s a Great Big Country” — maybe this song is actually Chinese? Would a real Chinese song be that much different? If I like this song, does that mean I am somehow Chinese, too? Or Russian? Who am I, anyway? Borders between subjects and objects are erased — between everything at once. The hero shrugs off the Chinese, but his attitude is partly a reflection or even an encoding of how he views his own people and himself. Both listener and performer are imperceptibly drawn deeper and deeper into the “great big country.” A ruminated attachment to tea profiteering weakens the importance of more thorny personal dependencies. Suddenly it turns out that this song loosens the bonds of prejudice and partisanry, delivers a bracing shock to familiar, petrified views of reality. In its own quirky way, it works as a force of freedom from illusions. That is, it does what serious art and great spiritual masters do. It helps us live.

This song about China seems so strong, so universal, because it’s about all of us, about that united life in the big country of the world where we’d like to make our own paths — however we see and dream them. However it suits our souls.

Speak Your Mind