Natalya Gladoush

Photo: Oleg Nazarkin

In the large palette of festivals held in St. Petersburg, another has emerged. “Interfolk” in Russia is a meeting of folk ensembles from all over the world. The festival committee aims to familiarize audiences with the diverse creativity of different ethnic groups. Showing the harmony of variety, the festival’s organizers seem to put special emphasis on acquainting the audience with ensembles from the “hinterlands” (especially in the case of Russian ensembles).

One such group was the ensemble “Khezine” from Tatarstan. Formed in 2006, the group was in St. Petersburg for the first time. They performed with great feeling and enthusiasm. Coming to the festival for them is a revelation; they strolled the city, chatted with singers and dancers from other cities and countries, looked and listened, and talked about their own experience.

In translation from the Tatar language, the group’s name means “treasure.” The head of the ensemble, Dilbar Khaibieva, speaking of his collective, emphasizes, “We’re from the countryside, among us are farmers, teachers, club managers, all kinds of people… The songs we perform here are the ones we sing at home, whether they’re very old or just recently written. Who preserves these songs? The local people. We’ve known these songs since childhood. Our grandmothers taught us.”

I ask whether it’s difficult to support the group. Dilbar answers, “Rehearsals are our holiday. At the opening, we sang the Tatar folk song “O My Heart” and showed the ceremony of “bleaching canvas.” And at the closing, we sang the Tatar folk song “Allyuki.” We see this festival as a good thing; it’s a chance to share experiences, to see how others perform. Our costumes were specially sewn for us, but they’re our own, bold, national, with the right choice of colors…”

Added depth came to the program with the performance of the “KrAsota” ensemble from Novosibirsk. The collective’s head, Oksana Vykhristyuk, called attention to their repertoire, drawn from songs they’ve gathered on folklore expeditions. The old-style songs make a unique impression; something very real, native and penetrating can be heard in these chants. The same careful understanding of tradition has gone into making the costumes, which display a special beauty and elegance, with much deep red, the color of life and joy.

An equal revelation for many was the performance of “Narspi,” a Chuvash folklore and ethnographic ensemble from Ufa. The picturesque red-and-white costumes decorated with the national patterns, the folk and contemporary songs, the characteristic movements — all these things testify to this people’s ancient origins and culture. And on the whole, to the variety of Russia’s indigenous cultural traditions and peoples.

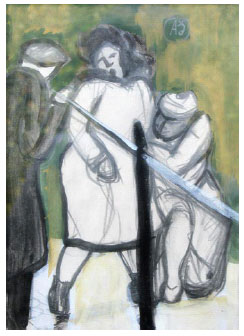

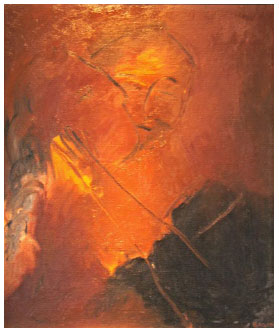

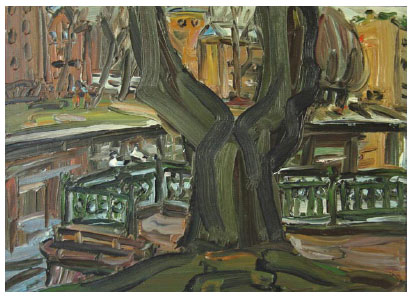

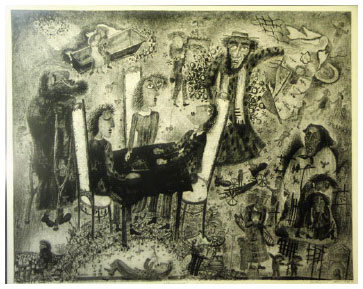

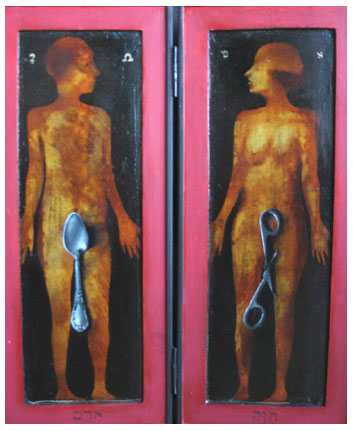

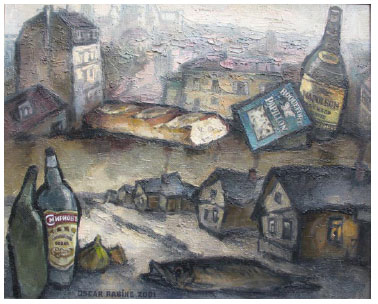

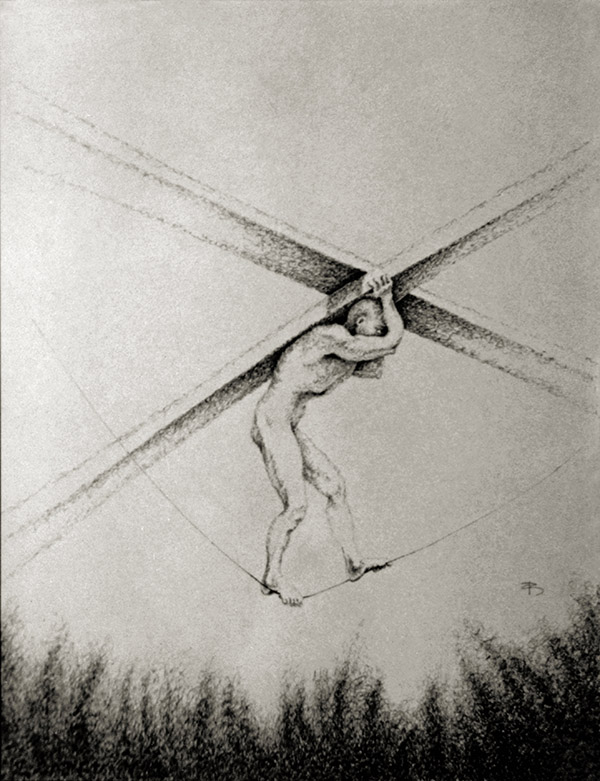

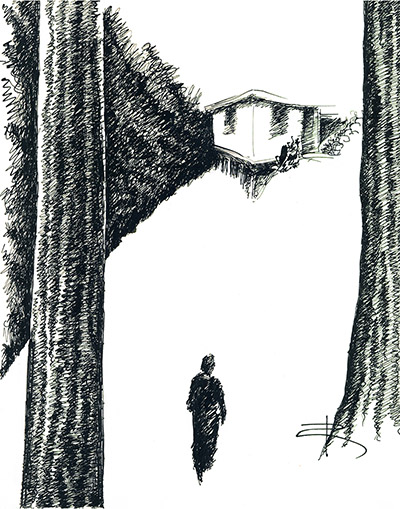

Scenes from the “Interfolk” festival

Part of my sympathies, of course, went to the Cossack vocal ensemble “Tal’yanka” from the village of Vaigaitsevo (Novosibirsk region) and the national folk ensemble “Vecherki” (Altai territory).

Certainly, I speak only of personal impressions. And the general conclusion they point to could be this: where tradition is supported, the folk arts flourish. Foremost, this could be seen in the festival’s Norwegian participants — the Bergen Kammerkor and the group “Strilaringen.” Refined movements, shining faces, cheerful courage… A whirlwind of joy felt by everyone in the hall. The same observation could apply to the guest artists from Greece, Sweden, the Philippines. Incidentally, the jury for the contest among the ensembles gave first place namely to the Filipinos.

But understandably, all this wasn’t about competition. It meant most just to see these living creations, to gaze again and again into the treasure chest of folk art.

The festival’s director and producer, Elena Bizina, describing the preparations for the festival, noted how much time went into developing the idea itself, as well as searching for partners. As the organizers see it, what in the concept for this new festival makes it especially different? It probably means most here to give the public exposure to authentic performances, to support those who have come from far away. It’s very important and necessary for people to interact with each other, to share their experience. There are also dreams of master classes, of ongoing meetings… Maybe a correspondence club, a virtual master class, could be organized as a personal — singing — network of folklorists, pursuing their discussions… There is huge interest in folklore; it’s not accidental, remarks Elena Bizina, that the competition for acceptance to folklore departments at institutes of higher education has intensified in recent years, and this fact has its own significance. In our conversation, Elena Bizina mentions the festivals held in the past, back in Soviet times, under the name and slogan “15 republics, 15 sisters.” Yes, those events were dry, schematic, but there was something rational in the idea itself. It’s namely in the provinces that native culture flourishes; these seedlings need the fresh air of supportive audiences, their approval. The new festival is a wonderful way to meet these needs, to give them a platform. “Behind the scenes,” the day-to-day life of the festival takes place, where its participants get to know each other, talk about the secrets of this or that manner of singing, discuss costumes, learn about the sources for knowing the traditions, about special literature, and, finally, gain new devoted fans for their creative work, make other special contacts…

When I learn that the Swedes carefully preserve their old costumes, that many Norwegians have their antique family clothing, true relics, it seems a shame that we Russians rarely have national costumes to hand down any longer. Fortunately, we do have access to excellent museum collections, and there recordings and photographs from the archives of famous gatherers of folk art, researchers of traditions of culture and daily life. So not all is lost, there are many opportunities ahead to make up for these omissions.

After all, the treasures of the folk spirit depend, as always, not on the price of gold, but on the broadness of your own heart.