Outsider, In Memory of Alek Rapoport: Angel and Prophet from the Streets of San Francisco

Published in: 11. Without and Within

Irina Kerner

The comparison of an artist or poet with a prophet hardly surprises, although the parallel often wants for justification. In certain ages, art takes this responsibility on itself, becoming the same revelatory form in which the Biblical word’s relevance emerges from unexpected angles. Namely this phenomenon marked the art of Alek Rapoport, who began his artistic development in nonconformist circles in the “Northern Venice” on the Neva and completed the movement of his life and work on the Pacific coast, on the steep hills of foggy, light-steeped San Francisco.

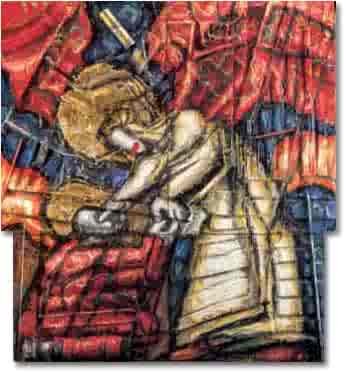

Among his paintings devoted to Biblical subject matter, a series of prophets occupies a special place. It is noteworthy that the prophets are all depicted at the moment of their appeal to the Creator, not to an audience. Angel and Prophet and Angel With Mask and Prophet show the prophet as a nearly fleshless skeleton. Here, he is a tormented spirit praying for insight. These prophets are not harsh preachers; they are no more than spectators, witnesses to the supernatural presence that makes them captive servants of heavenly commands.

A. Rapoport, Angel and Prophet

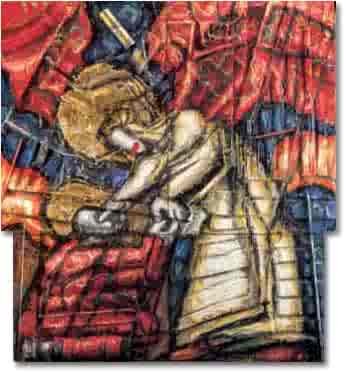

Regardless of the close compositional similarity, Angel and Prophet and Angel With Mask and Prophet represent prophets in two quite different conditions. Angel With Mask and Prophet describes the beginning of the prophet’s birth, the act of his consecration. The human is awed by the Angel’s appearance: he accepts the scroll in a motion full of doubt and bewilderment. Having no wish to blind the unprepared son of man or frighten him earlier than necessary, the Angel shields his face with a mask. Here is shown a stage when the human is capable of assenting to an order to act, while not yet divining the sense of it.

A. Rapoport, Angel With Mask and Prophet

Angel and Prophet gives this scene a quite different connotation. In the painting, the prophet is now ready for the Angel to appear in any form, whether as messenger of death or herald of the future. The angel here is no chance vision, but is the literal embodiment of what the human will readily submit to, not by blind error or compulsion, but of his own volition. The prophet’s consciousness has awakened, and it is he who turns to the Lord in prayer, calling on him for salvation.

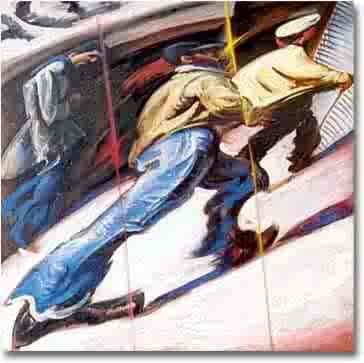

Within the Biblical cycle, the subject of Samson Destroying the House of the Philistines commands special attention. The painting centers on the image of the prophet engaged in a struggle to understand and delimit what is possible for him. His movement in seizing the pillars bespeaks a desperate attempt to break through the bounds of human consciousness and thought. He is a hero in rebellion, in uprising—not against the God who has “abandoned him” but against the Philistines, the mythic enemies who have enticed him to his downfall. For the prophet, the mission from God means a chance to rise to a new height, to come to a deeper knowledge of the Creator; a chance that always brings a human in conflict with himself. He rises up against himself. For God’s chosen, it may be the hardest, highest errand God can offer. Even historical transfigurations fade onto a secondary plane before this task; it lets the human know himself on a new scale.

A. Rapoport, Samson Destroying the House of the Philistines

The prophet cannot have personal enemies. His enemies are “people who do not know God.” In visiting justice on the enemy, he thus merely embodies a willing tool; he remains an instrument of a higher power. The gift of his strength is impermanent, not to be looked to attain personal immortality (even in history’s annals), still less for salvation.

In vanquishing the Philistines, the Biblical Samson appears heroic to a very relative degree. A true hero’s majesty and clarity of vision become evident in him only at the end, at the moment of parting with life. Samson attains insight namely upon losing his strength. When agonistic suffering becomes the drama’s center, the prophet rises to become a representative for all of humanity, speaking alone for all people before God’s face.

The lone human soul seeks salvation on its own when God refuses to help it. For the prophet, however, this is not a personal drama, although he has a part in it. Heroism on history’s stage is just his assigned role, and he plays it from start to finish. Yet the actions themselves remain past his conscious concern, beyond historical processes.

A characteristic detail: in the paintings, the prophets never interact with the viewer, never turn their gazes toward him. Maintaining an unbroken dialogue with the Creator, the prophet has no distractions; for him, the whole expanse of life is filled with the divine presence.

It was not likely by chance that the artist chose the moment in the Biblical narrative when the human stands at a crossroads between two worlds, between two spaces with different measures. To keep from becoming a slave to his own fate, the human must resolve inner conflict as an independent being, so God casts him aside to let him come freely to radical self-definition.

The Biblical event of Samson’s death, however fatal, is at once not the sole potential outcome. By contrast, in the painting, the hero’s dismay and terror are channeled into a single concentrated burst that mobilizes every part of his remaining strength. Stone even gives way to human hands, but what strength must a human command to step past the barrier shutting off his awareness from objective truth?

Truth means a great deal to the artist. The prophet’s word stays on for centuries (although forgotten, namely he is then returned to). Like a work of art. Real truth cannot be of narrow significance, and no standards will apply to it. The artist dictates his own standard. And does so, of course, from his own position.

A theme always remains timely, but it takes on different appearances at different times. The artist could rightly be said not to provide commentary on the theme so much as recast it in a new form. In this regard, I have in mind not a process of reconstruction but rather the artist’s infusion of the original with sense and meaning, whereby it acquires new expressiveness.

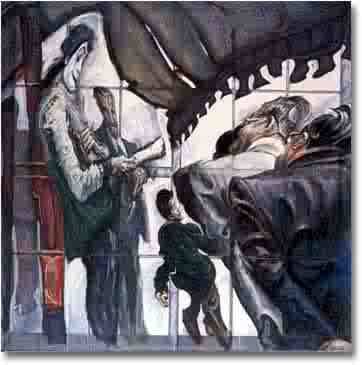

A. Rapoport, The Angel Opens the Prophet’s Eyes and Mouth

The work entitled The Angel Opens the Prophet’s Eyes and Mouth is very interesting in this light. The Angel seemingly performs a kind of anatomical dissection, separating the skull from the immortal soul, thus changing a dead man into a living one.

It happens to be characteristic of the Bible that this transformative process is almost never described concretely. It is all but free of even hints at what a human submits to in choosing self-renunciation for the sake of the higher goal of servitude. And yet the artist uses the magic of his intuition to reveal what the Bible leaves unsaid. But not only this. The Biblical subject matter is no longer exceptional to the Bible, taking on the imprint of a personal relation and a personal conception as well. Recasting the Biblical language in a concrete, modern interpretation, it becomes a simple matter to recognize the prophet as personifying the artist in his search for salvation in art.

While occupying a significant place in Alek Rapoport’s work, the Biblical theme is not the artist’s only subject. He has a large number of works dedicated to ordinary life. An exceptionally strong and fresh impression is made by the cycle Images of San Francisco, which interweaves a series of street scenes. Even a perfunctory glance at the two distinct, contrasting thematic directions reveals the fundamental difference between them. If in the images of prophets dynamism is conveyed through the expression of deep feeling, in Images of San Francisco it is embodied in the world-spanning panorama of a shifting mass where all pulses with a single rhythm.

Images of San Francisco could be said to reflect the same public the artist turns to through the prophets. Whereas the prophet is situated in eternal antagonism toward commonplace consciousness, the artist himself exists as a binding link between them, joining the prophetic spirit and the lower side of being through the single idea of art. And if the prophet’s position relative to the audience is categorical and devoid of sympathy, the characters of Images of San Francisco are found worthy of the artist’s mercy. For him, they are people who know nothing of any reality past the confines of daily routine and pedestrian interests, on a different scale.

A. Rapoport, Yellow Cabs and Warehouses

A. Rapoport, South of Market Warehouses

It is perhaps when the paintings’ subject matter veers away from signs of human presence that the artist’s view of San Francisco is voiced most openly. For example, the painting South of Market Warehouses, with its solitary line of cars, expresses a reality of desolation and loneliness in a pure, unobscured form. In another work, Yellow Cabs and Warehouses, taxis creep slowly along wet asphalt, establishing the tone for an overall movement where everything heads the same way, never stopping, undistracted.

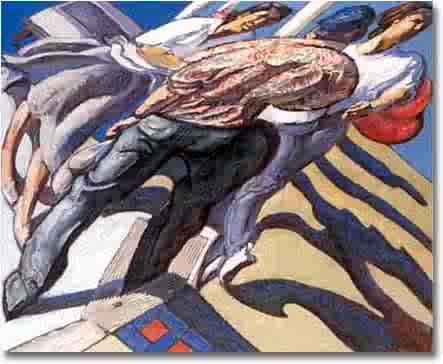

An impression arises that the realist manner of the cycle’s execution was suggested by the artist’s wish and need to “bring the dead to life.” While the day-to-day scenes comprise a precisely defined picture of American life, the artist’s realism employs elements of the grotesque. The canvas Three Men on Market Street appears symbolic, with its gigantic, outstretched stride a seeming attempt to overstep the edge that sets the surreal apart from reality.

A. Rapoport, Three Men on Market Street

A. Rapoport, Tourists in San Francisco

The subject matter of Tourists in San Francisco may be assessed as key in many ways. The composition counterposes token tourists and a local pair; one is a mime. The polite admiration described on the guests’ faces meets with dutiful welcome from their world-wise servants. Like the tourists, the hosts are not individuals but types, split among various groups. There is no common tie among them. The tourists move past their hosts as if passing by mannequins. The absence of interaction among personalities forms a band dividing the space between them. An effect of particular disjointedness arises due to the fact that no one here seems to distinguish between friends and strangers. It is characteristic that one of the representative San Franciscans in the painting is a mime in greasepaint. His monotonous, frozen smile escorts all visitors, addressed in equal parts to tourists and to empty space.

A. Rapoport, At Union Square

At Union Square is one of the few paintings in the series to feature a human face as the compositional center. A passerby’s face, turned to the viewer, is illuminated by a momentary flash, set apart from the panorama of a cold, gray day. Behind him can be seen the corner of a skyscraper; to the side, pedestrians. The luminous face in the fog elicits a momentary interest in the individual who unexpectedly assumes living contour against the drab background.

A. Rapoport, Latinos on Mission Street

It is notable that the images’ surreal quality stems from the fact that they are nearly all impersonal. Although the characters interact among themselves, a palpable distance is maintained among them. In the painting Latinos on Mission Street, for example, the meeting place of the three passersby above all recalls a desert or the field for a relay race where each of the three has his own lane: their roads are without points of intersection. Is it not because they are all “tourists,” their appearance in the world a brief instant leaving only a pale glimmer in the current of eternal motion? Though strangers to each other, they are the only true exhibits of the museum where they found themselves, to be seen by the artist who bestowed them with a title, Images of San Francisco.

Irina Kerner

Speak Your Mind