An Artist’s Celebrations: Benjamin Kletzel’s Exhibit in Jerusalem

Published in: 16. Family and SlaveryIrina Kerner, Israel

Benjamin Kletzel

I met the artist Benjamin Kletzel at an exhibit of his Jerusalem. I had never seen his work before and never even heard his name. Having learned that I was interested in painting, he invited me to visit his studio.

His simplicity, unassumingness and attentiveness to others immediately endeared me to him. Nevertheless, I didn’t dare to call him right away — either out of timidity, or out of fear of being disappointed. You don’t often meet good artists.

Still, after a while, I arranged to meet with him.

His workshop is located in the city center, in an old two-story house. The lower floor is occupied by a furniture restorer. “What a charming neighborhood,” flashed through my mind, “an artist and a craftsman …” Climbing the stairs to the second floor, I saw a sign with an inscription: “KNOCK.” For a moment my breath caught in my throat, as if there were some secret hidden behind the door. I knocked carefully. And then I heard an affectionate: “Come in!…”

I entered and froze. On the walls, shelves, on the floor, everywhere — paintings, and what paintings they were! … It was as if the door to an unusual world had opened, unlike anything else.

The themes of the works are varied. Still lifes, landscapes, portraits, compositions with animals and people coexist here. The technique is also varied. A pungent oriental flavor is combined with muted, restrained tones. It is hard to believe that all this belongs to one brush.

The workshop is bright, spacious and very comfortable. There is not much furniture in it: a table, a sofa, a small bedside table. On the table are items that can be used to work from life — however, this is mainly needed by his students. The artist himself never works from nature. All his works are created from imagination or memory.

The proprietor takes out paintings one by one, shows them and then quickly returns them to their place. There are so many works that a day would not be enough to study them all. I have to content myself with fleeting impressions.

In the workshop, there is a golden frame especially for demonstrations — a kind of tool for evaluating the work. In this frame, he says, the painting immediately wins.

In some cases, it seems to me that a simpler frame would be more in harmony with the mood of the painting. However, an artist’s attitude toward his works is an intimate matter. It’s like caring for a woman you love, whom you want to dress more elegantly.

The proprietor’s kindness and childlike innocence are very captivating. He places the newly finished canvas in the middle of the room, closer to the light, and says, addressing either me or himself: “Well, how about it? Is this possible to look at?”

He is interested in my opinion about his works, not hiding what he thinks about them himself. His confidence is touching. About one of the paintings, he frankly declares that he doesn’t like it. “That face is a little too static…” he says. There is something doll-like in the look of the salesman’s round black eyes on the canvas. His whole appearance testifies to strength, health; this is the real son of the market.

One of the artist’s most recent works was painted during a visit to a friend living in the north of the country. A large face occupies the entire canvas. Behind are mountains. It seems that the appearance of a human face is a surprise for nature. It seems to violate an age-old order.

Another motif that appeared at the same time is a cellist. The barely outlined contour of the figure with the instrument almost merges with the dark red background. The musician seems to dissolve in the sound, creating a feeling of peace.

Somehow in a special way I recall the image of a fish against the backdrop of the urban landscape. Unlike other works, in which the presence of a fish is only part of the composition, here it is the focus of the artist’s attention. The appearance of a fish in an alien setting looks intriguing.

The work “Musicians in the City” is original and unexpected. The sight of artistic people in an urban environment is invigorating, as a sign of something alive, atypical.

In the artist’s canvases, one feels a special connection with the earth, with the origins of wisdom. Even the theme of loneliness, which often appears in his works, doesn’t evoke a sense of pessimism.

“I’m a realist,” says Kletzel.

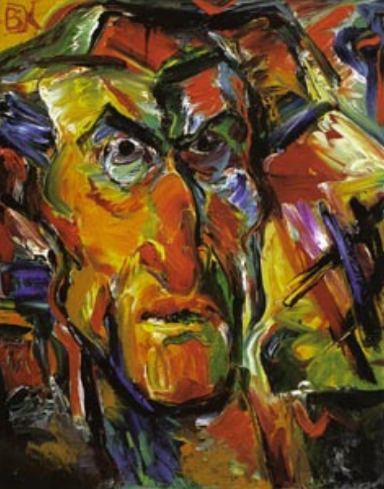

A Picture Painted in the North

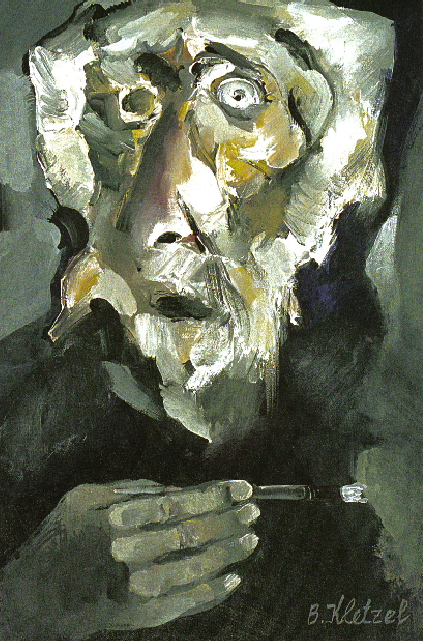

The realism of Benjamin Kletzel is not in the accuracy of the image, not in the details, but in his penetration into the essence of nature. His portraits are often exaggerated and reach a level of sharp (but never rough) generalization. The portrait of the poet I. Guberman is very expressive. The poet looks like both a fighter and a clown, but maybe this is just a mask hiding irony?

It can be said about the works of B. Kletsel that they give an idea not so much about the character of a person, but about his condition at a certain point. One interesting example is “The Sick Artist.”

There is detachment in the gaze of the bedridden artist. But at the same time — meek humility, acceptance of the natural end of life.

The contrasts of red, yellow, green create an aura of the artist’s inner world. In fact, here before us is the experience of a lifetime, the fruit of a long creative journey.

Everything that attracts the attention of B. Kletsel arouses keen interest in him. He does not criticize people, but shows them as he sees them, trying to bring out their best qualities. In portraying the scene of a poker game, he ignores the pettiness inherent in gamblers. In the eyes of his players is tense expectation. And although it is clear that they have far from noble motives, it is easy to imagine the same people waiting for heavenly revelation.

This does not mean, however, that the artist has the same attitude towards all phenomena in life. Comparing his portraits with subjects dedicated to scenes of everyday life, it is impossible not to pay attention to the level of depth, which varies depending on the object under study. For example, the artist sees the biblical Joseph in a completely different way than ordinary believers. His Joseph is a martyr. The eyes are half closed; the gaze is directed inward, into the self. For him there is neither time nor space; there is only pain and suffering. But in this detachment, one feels inner strength, the capacity for spiritual insight.

Poet Igor Guberman

The paintings depicting religious Jews look different. “Le Chaim!” is a canvas depicting a Sabbath meal. It all comes down to the charm of the celebration, the “love of the happy moment” when the believers feel as one. The artist finds charm in this because such moments give a person an opportunity to feel engaged with the mysteries of life. And for the painter himself, real life amounts search, creativity, dedication. Depicting artistic people (among whom an important place is occupied by artists themselves), B. Kletsel creates images people able to transform the world around them. Most of these portraits show a creative person deep in reflection, at the moment of the beginning of creativity. “An artist constantly writes and draws,” says B. Kletsel. “He doesn’t necessarily pick up a pencil, but he thinks and reflects all the time.”

In “The Local Artist”, the seated artist, who occupies the entire space of the painting, looks like an alien. It seems like he will never get up, will not go anywhere else, because this is his place, his own, the world that belongs to him alone.

The Local Artist

Poker

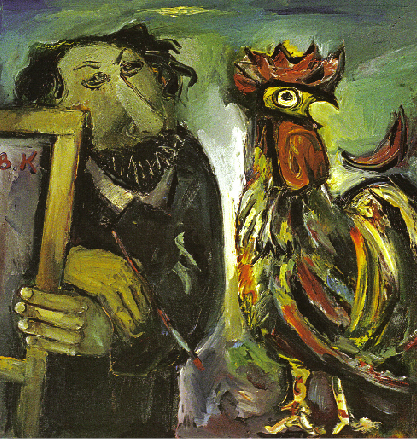

Artist and Rooster

The hero of the work “The Artist and the Rooster” carefully studies a bright, picturesque rooster. However, beauty in itself is not yet a reason for creativity. You can see that the artist’s gaze glides past the rooster. Maybe the rooster we see here is a new artistic creation. Or maybe two creators at once — nature and the artist — took up the brush in parallel.

In “Rumination,” the artist’s relationship with nature is shown differently. Here we see a man sitting at the table, immersed in deep thought. On the table are familiar attributes. The palette, fish, wine are the favorite objects of the painter. But now he doesn’t need them. His only tool is his head. Creativity is impossible without thought.

Rumination

The Artist Leon Mayer

It is probably no coincidence that a creative person sometimes feels the need to forget about his craft. “The formation of an artist is a long process,” says B. Kletsel. “Why should there be intervals? We must forget our works. Improve. With each period, drop by drop, something is added. The main thing is to be yourself.”

Love of the ordinary is combined with the artist’s ability not to depend on what causes familiar associations. His world is not as simple as the world of those of his characters who can be found on the street or in the market. If these worlds intersect, it is most often due to a happy accident, for example, when the artist is walking around the city or looking out the window. He says that sometimes a little thing noticed during a walk can cause a new image to appear.

It elicits particular sympathy that the earthly characters of B. Kletzel, transferred from the street to the canvas, are drawn into the reality that is practically unknown to them in life.

In “Nachlaot,” two women, with their backs turned to the viewer, are watching a red crescent moon beyond the fence of a one-story house. Walls do not shelter a person from the all-pervading city. The crescent moon glowing in the dark is a spark of hope, a small reminder of eternity.

Nakhlaot

To Prayer

One might think of the “Watermelon Eaters” that they are seated to perform some kind of sacrament. They hold slices of watermelon carefully, carefully, as if they hold a magic tool in their hands. As if they are waiting for this “tool” to unlock an invisible door for them.

The painter B. Kletsel is not fond of analysis. His engine is intuition. Although he himself often evaluates his works in terms of technique, they contain interesting, deep thoughts. His works give freedom to the imagination of the viewer, without limiting the possibilities of interpretation.

Some of the artist’s works, written simply from the heart, under the impression of some episode, evoke a mystical feeling. One of them is “To Prayer.” The painting shows the figures of people heading to the synagogue. Looking at them, one might think that these are not people, but mountains rushing towards the light. “Once I saw religious people on the street. Suddenly — the wind, well, it was like a storm!.. It billowed his coat! That led me to something…”

In the artist’s works, one can see not so much an ideological development as a change of mood, depending on which a feeling of joy or deep thought remains.

“Sometimes you want a celebration,” Kletzel says.

Working in the studio, the artist makes every day a celebration, marking it with the appearance of a new work. You sometimes feel the same sense of a celebration when you walk around Jerusalem. The works dedicated to Jerusalem are like a dream of a non-existent city. The streets of Jerusalem on the canvases turn into a mystery.

This secret is the author himself. He doesn’t care how others feel about his beloved city. He finds there what he needs — that’s enough.

The artist devotes himself entirely to his work. This quality is typical for his characters. Its fishermen hold fish like an artist holds his palette. It doesn’t matter what the person is interested in. Passion, dedication, love of life — that’s what’s most important.

At Benjamin Kletzel’s exhibition at the Jerusalem Cultural Center on March 23, 2009

The artist Benjamin Kletzel speak about art:

- I believe that above all there should be painting. That is expression. The feeling that you splash onto the canvas. You work not for someone else, but for yourself. You are your own critic.

- Some tasks are implemented, some are not. The process itself is important. I take a brush and work; that will work — this will work, no — no. Maybe this process is also a joy. The main thing is to paint with talent. Everything must come from the heart.

- I think painting is arranged like music. Remove one smear, and everything falls apart.

- The main thing is to reveal your nature. Get your doppelgänger out.

- What is intuition? It’s erudition. Accumulation. Knowledge of psychology, etc. In the process of work, you open yourself.

- The purpose of art is to purify a person.

- The artist exposes himself.

- During socialist realism, the bulk of artists worked visually (not comprehending, but copying nature). Socialist realism gave only skill.

- The artist must be sincere, honest — first of all to himself. Goya, Velasquez painted because they couldn’t help but paint. And then, too, there was dictatorship. The artist is always under pressure.

- All sicknesses go away when you stand in front of the easel. There are things you have to paint. It happens that you hatch some kind of plan but it isn’t realized. Sometimes you start to paint realistically, and then you refuse to do that. The challenge is to bring out the light from within.

- If you repeat what you see, it will be boring. We must do it differently.

- Where does it come from? I saw something somewhere. For example: I was at the market, I saw oranges, watermelons. Spots… Some kind of trifle. Everything. Enough.

From the window I saw a strip of the sea. And it already pushed me to something. The object itself is unimportant. Everything engages me. Through an object, I express a state. Maybe this doesn’t concern global things, but just the everyday. - A basis for assessment: the painting should be interesting, not beautiful.

- Painting is a quiet thing.

- I support things being modern, belonging to the era in which you live.

- Breaks at work? Only if I get sick or go somewhere. The artist constantly paints and draws. He does not necessarily pick up a pencil, but he thinks and reflects all the time.

- Returning to subjects? You handle the same subject in a different way every time.

- Everyone is learning. There must be an environment for formation. The formation of an artist is a long process. You need to improve. So that your sweat, efforts are not visible. With each period, drop by drop, something is added. The main thing is to be yourself.

- There are artists who orient according to their time. I am far from that. I do what I see fit.

- I can’t imagine what I’m going to paint. The painting is born in the process of work.

- Why should there be intervals? We must forget our works. When you paint, it’s a different life.

- If you admire your works, then that’s your ceiling.

- I don’t divide people into those who understand and those who don’t. But what you do, you do primarily for artists. Artists understand better.

- I’m engage in what is happening in the world. I sympathize with people. Therefore, I often paint gray, pessimistic things.

- I need peace of mind. It’s great to have someone around to help you. Love must grow. I’ve always liked that my wife sings. That she’s a personality, a person of art.

- I am never satisfied with my works. I sell my works relatively cheaply. I don’t like money at all.

- Everything has to be aesthetic. My ancestors were tailors. Every good craftsman is an artist.

Speak Your Mind