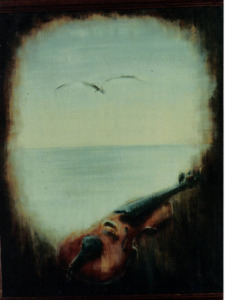

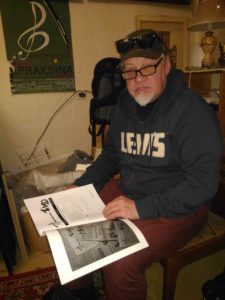

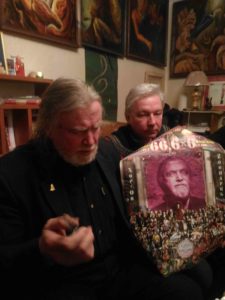

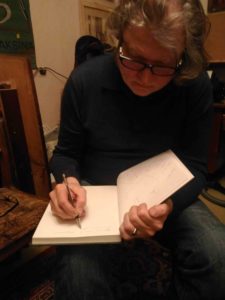

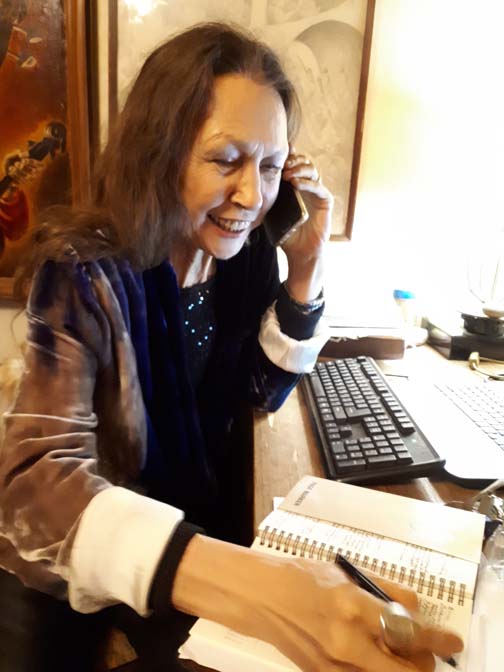

November 9-11, 2019, St. Petersburg, Russia. Editor in chief Tatyana Apraksina and AB supporters in the Apraksin Lane editorial office.

DSC01711

DSC01711

20191110_201441_a

20191110 201441 B

20191110 201441 B

20191111 012332 57962126525094

20191111 012332 57962126525094

20191110 201721

20191110 201721

20191110 201524

20191110 201524

20191110_200246

20191110_200238

20191110_200235

DSC01709

DSC01709

DSC01708

DSC01708

DSC01707

DSC01707

DSC01706

DSC01706

DSC01705

DSC01705

DSC01704

DSC01704

20191110_200130

20191110_195902