Old and New “Sakhalin Rock”

Published in: 19. The School of Anonymity

Kumiko Uyeda

Kumiko Uyeda received her Ph.D. in Cultural Musicology from University of California, Santa Cruz. She earned her Masters in piano performance from the Manhattan School of Music in New York City, where she was an active participant in contemporary music. She has worked as a cross-disciplinary musician in fields including Western art music, jazz, poetry and indigenous musics. Since resuming her academic career, Kumiko has pursued research on Japanese film music as well as the music of the Ainu.

1.

The Ainu woman dressed in traditional clothing steps up to the microphone and begins playing the mukkuri, a bamboo mouth harp. The design on her cloak resembles an Escher-like pattern and she wears an embroidered headband across her forehead. I am an audience in a cultural presentation at an Ainu museum in Hokkaido, Japan. The audience is equally divided between Japanese and South Korean tourists, sitting inside a replica of a traditional Ainu house with dozens of smoked salmon hanging from the high ceilings.

As she begins to play, the twanging timbre from the mukkuri, a mouth-harp, elicits girlish giggles from the audience, seemingly from the Japanese tourist sector, but it is quickly silenced by the sober demeanor of the performer. Keeping their tradition alive is serious business for the Ainu people; they have experienced three hundred years of military defeat, territorial loss, political and economic subjugation, and social discrimination from the Japanese and, to a much lesser extent, the Russians. However, despite Japanese governments efforts in assimilation, the Ainu have maintained their cultural identity, making significant steps in recent decades. The Japanese government formally recognized the Ainu in 2008 as an Indigenous Culture in Japan, a notable event — since the Japanese government had outlawed Ainu language and cultural expressions in the early part of the twentieth century.

Who are the Ainu? Much of the world is unfamiliar with this native people of northern Japan. “Ainu” literally means “humans,” and their term for the Japanese is “Wajin,” or “neighbors.” Studies show that they are direct descendants of the Jomon, the prehistoric people of Japan. While the early Ainu remained relatively isolated, the Japanese ancestors became intermingled with mostly Korean and Chinese people and cultures, developing into the Yayoi culture after 300 B.C. and eventually forming the present-day Japanese population.

The traditional Ainu before 1900 had long flowing beards, large stature and deep-set eyes, while the women wore striking lip tattoos, making the Ainu appear very different from other Asian populations. Their territory in the nineteenth century stretched from central Sakhalin Island and the southern tip of Kamchatka Peninsula to northern Honshu (main Island of Japan), before being absorbed by Russia and Japan.

When the new Meiji government in 1868 adopted modernization measures, Japanese citizens were encouraged to immigrate to the relatively unpopulated northern island of then “Ezo,” renamed Hokkaido, to exploit Hokkaido’s natural resources. This resulted in a land rush, with newcomers flooding what until then, except for Japanese outposts and a few fishing stations, had been the sole provinces of the native Ainu people. Rapid colonization measures followed, and the Ainu, who mostly relied on hunting and gathering, found themselves without means for their livelihood. The Japanese government instituted forced labor camps for the Ainu in logging, mass fishing, and railroad building.

2.

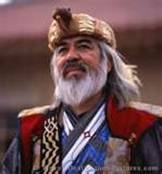

An Ainu man, also dressed in traditional clothing, approaches the audience to speak about the historical background and cultural insights of the Ainu tradition. He began his talk with “I am Ainu.” To the majority of the Japanese audience, this simple statement might have equated to “I am a space alien,” with the unfamiliar concept creating more questions than answers. Indeed, the Ainu have assimilated so thoroughly into Japanese culture that most of the contemporary Japanese public is unaware of their presence. There are presently 20,000 registered members in the Ainu Association in Hokkaido, but due to discrimination in schools and the workplace, many Ainu people do not disclose their heritage, and a more accurate number of Ainu descendants is estimated at around 200,000.

The Ainu community comes together for the many ceremonies and rituals such as the Iyomante (the bear spirit sending ceremony), the salmon ritual, swordfish ritual, and Shakusain Memorial, just to name a few. Distinctive prayer sticks, or ikupasuy, and inaw, shaved sticks that serve as messengers to the gods, are used in the ceremonies and rituals. In traditional Ainu belief, every living thing and every being, whether animate or inanimate, is a god and a visitor to earth from the god world. Because these gods spend time on earth and make their material forms available to people for food and livelihood, the people must use them with respect and return the spirit to the god world with a ritual spirit-sending ceremony. The most elaborate “sending” ceremonies are reserved for the chief Ainu deities – bears, owls, and foxes – but even spirits of small animals like songbirds or seemingly inconsequential objects like a broken kettle or knife may have its spirit sent off to the god world with a special prayer.

The Ainu language was passed down through generations as an oral tradition, with the phonetic Japanese writing applied only in the twentieth century. The tales of heroes were told through yukar, Ainu epic poetry. The narrators traditionally recited stories while lying down and looking up, but more recently, both narrators and audience sit together and beat the wooden hearth frame with a stick called a repni. The audience shouts “Het! Het!” to create rhythm and to encourage the narrator.

Some dances have competitive elements: two people or two groups face each other and compete to see which side can continue the vigorous dance the longest. Such competitive song and dance is found in various northern ethnic groups. The “throat singing/game” of the Sakhalin Ainu involves two women sitting and facing each other, each player making a megaphone with her cupped hands and connecting the ends of the “speaker” to her partner’s. Then they begin making sounds into their opponent’s mouth by closing their throat and aspirating strongly. Similar games are found among Eastern Canadian Inuit and Siberian Chukchi. The Japanese ethnomusicologist Tanimoto Kazuyuki writes that the throat-singing games might have had shamanistic origins, since the Ainu believed that throat-singing had the power to call the god who could scare away such epidemics as smallpox.

3.

Today, the Ainu language is not spoken in daily life, the last of the Ainu native speakers having passed away in the past decade. However, the Ainu language and culture are kept alive through Ainu ceremonies, rituals, and performance groups active in Hokkaido. There is now a revitalization of cultural expressions in the Ainu, especially in music. In the past decade, younger generations have spearheaded the resurgence in the arts within the Ainu community, performing historical dances and songs, forming contemporary musical groups, and blending outside influences such as electric instruments and the reggae genre with traditional Ainu elements.

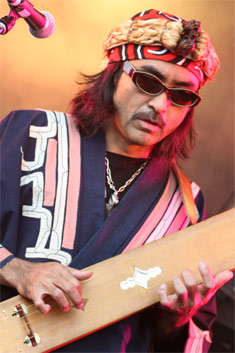

Some Ainu groups formed in the last decade included Marewrew, composed of four Ainu women vocalists; Oki Kano, an Ainu musician who performs the tonkori (traditional, unfretted, plucked zither) in his band Ainu Dub; and Nikaop, an Ainu group that aims to recreate traditional dances and songs reconstructed from old field recordings and videos. Based in Sapporo, Hokkaido’s capital, Nikaop is mainly made up of of 20- and 30-year-old Ainu musicians and dancers. Oki Kano has been performing the tonkori for eleven years. He formed the band Dub Ainu in 2006, and the group has just released their third CD, “Sakhalin Rock.” All of Oki’s songs are sung in Ainu, and during his performances he speaks about Ainu history, rituals and spiritual perspective.

In a July 2010 interview, Oki says there are “messages for the indigenous cause” in his songs, although they are not meant to “agitate the people,” but rather as “sharing certain personal feelings.” For Oki, music is a way for him to convey the Ainu struggle, which contains internal as well as external issues. “Think about the black man fighting other blacks in the Bronx,” says Oki. “We have similar issues within the Ainu.” I wondered out loud if the forced subjugation might have something to do with Ainu’s problems, which are not unlike those of other indigenous groups, such as Native Americans. The Ainu internal struggle is not publicized much, given the anonymity with which the Ainu function in Japanese society. What identifies the Ainu to the larger society, as well as to themselves, is the public music and dance performance that carries their tradition, language, and points the way to portray who they are.

Speak Your Mind