Caprices of the Evolution of the Louvre

Published in: 30. On the Way

P. Walton

We have all heard of the Louvre, the most famous art museum in the world, hosting millions of visitors each year. What not everyone realizes is that the Louvre was not always an art museum, nor even simply a royal palace. It began life as a fortress to protect the French from attacks by the English, and its ongoing construction over the years closely followed English-French relations and shared concerns.

Photo: Sasan Hezarkhani

French King Philippe Auguste (1165-1223), fearful of English attacks on Paris, first built a great wall around the city. Then, in 1190, about to depart on crusade, he ordered the construction of a defensive fortress. That fortress was the Louvre.

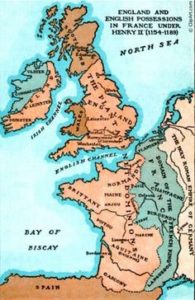

The English were a constant threat at that time. Unlike in later years, the English were not sitting harmlessly on the other side of la Manche, but also on the European continent.

When William the Conqueror took England in 1066, he retained possession of Normandy, which nominally remained the French king’s vassal after becoming a part of England. Then, when the White Ship sank in 1120, killing the sole male heir of William’s grandson Henry I and leaving his daughter Mathilda to inherit the crown, the English barons refused to accept a female ruler, rallying instead around her cousin Stephen of Blois, which resulted in a civil war, at the end of which Mathilda’s son Henry became King Henry II. This meant that, along with the king, England received the French lands of Mathilda’s husband, Geoffrey Plantagenet of Anjou.

Mathilda, Queen of England

Meanwhile, the always resourceful Eleanor of Aquitaine had persuaded King Louis VII of France that their marriage was not blessed by God, as evidenced by their having only female children. On that basis, she managed to get a divorce — and so was able to marry Henry II, to whom she brought her enormous territory of Aquitaine.

So by the time of Philippe Auguste, the English had possession of Normandy, Anjou and Aquitaine (shown on the map below as “The Plantagenet Dominion”) — that is, about half the territory of today’s France! Philippe Auguste thus had good reason to build a fortress in Paris.

Over the years, the fortress grew into a royal palace, but fighting with the English continued, so the royals moved out of Paris, which was just as well, because the English did finally manage to take the city in 1420.

Not until the reign of François I (1515-1547) did a French king return to the Louvre, whose construction he continued, beginning work on a new wing — called the Lescot Wing after its architect — and modernizing the entire building: the windows and doors were enlarged and the living quarters refurbished, giving the palace the appearance of a chateau worthy of the Italian Renaissance. He tore down the original Great Tower, perhaps a sign that the French were no longer worried about English invasion by then, having fought the English off most territories on the continent.

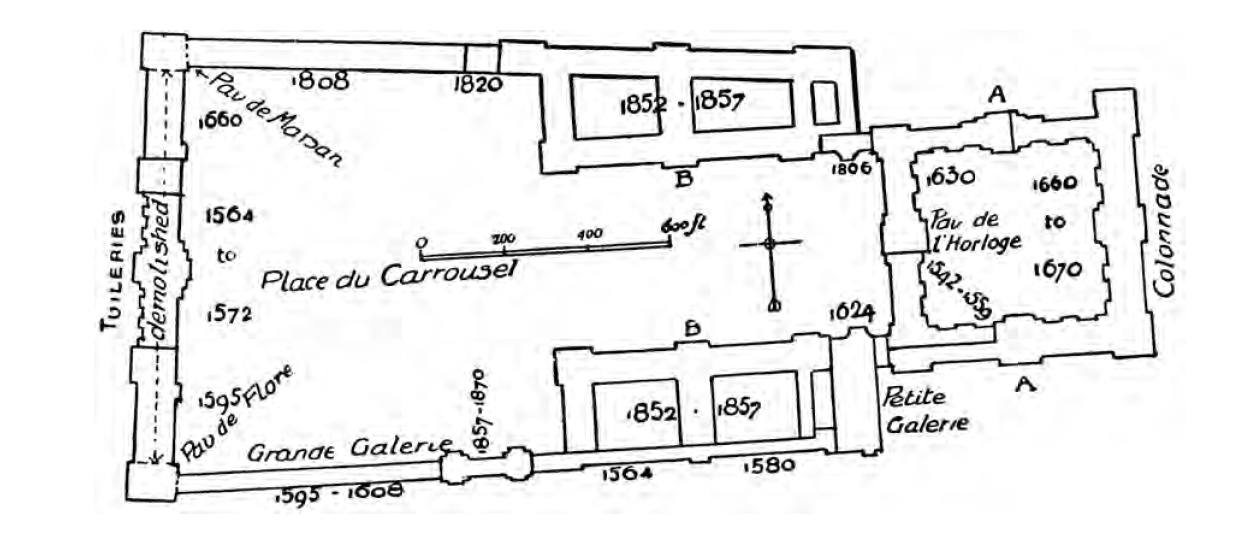

The illustration below shows work done on the Louvre since that time.

After the years of harassment by the English, François also sent a little payback in the form of a young Englishwoman, Anne Boleyn, educated in his brilliant court. Anne returned to England to enchant the English King Henry VIII (1509-1547). Henry’s Spanish wife, Catherine of Aragon, had failed to deliver him a male heir. We’ve already seen the importance of such small details. Henry became desperate to divorce Catherine and marry Anne. While a previous Pope had granted Louis and Eleanor a divorce, the current Pope would not do the same for Henry. So even though Henry had been a big defender of the Catholic Church when Martin Luther had nailed his 95 theses to the church in Wittenburg, Henry broke all ties with the church to marry Anne, making England Protestant. All this resulted in rather a lot of turmoil for England, including the eventual execution of poor Anne when she, too, failed to provide a male heir.

Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn

François’ son Henry II, despite a premature death as a result of a jousting tournament, managed to complete a new wing of the Louvre. He also sent a parting shot at the English, in 1558, by finally kicking them out of Calais — the last small English foothold on the continent.

Henry’s son François II did not add to the Louvre, being sickly and dying after only a little more than a year. After his death, though, the French sent a little more trouble to the English in the person of his widow, Mary Queen of Scots, who challenged the throne of Elizabeth I — England’s second queen (1558-1603), with no male heirs available, she became possibly its most beloved ruler ever. Mary threatened to stir up England’s Catholics against the country’s new Protestant faith. All this ended, though, as it had with Anne, by Mary getting her head chopped off.

François II of France and Mary Stuart

François was succeeded by his brother, Charles IX, in 1560, but since Charles was only 10, their mother, Catherine de Medici, became regent. She undertook great works on the Louvre. She built the Tuileries Palace and gardens that still bear that name today. Meanwhile, though, France was by now having its own troubles with religion, and Catherine is thought to have been behind the plot, under the pretext of her daughter’s wedding with the Protestant Henri of Navarre, to lure Protestant nobles to Paris only to have most of them killed during the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572.

Fortunately for the Louvre, the newlywed Henri himself was not killed. Following the reign of Catherine’s last son, Henri III (1574-1589), Henri of Navarre became Henri IV (1589-1610) and went on to further Catherine’s construction work, beginning a 400-meter-long Grande Galerie leading from the Louvre to the Tuileries Palace. He also brought a temporary end to the religious wars in France by 1) converting to Catholicism, 2) famously saying “Paris is worth a mass,” and 3) signing the Edict of Nantes in 1598, granting Protestants in the country a degree of religious freedom. Unfortunately, his demonstrative conversion left some unconvinced, and in 1610 he was assassinated by a Catholic.

Catherine de Medici

Henri’s son Louis XIII (1610-1643) added the Clock Pavillon to the wing built by François I, and built the Sully wing. He also, with the aid of the “Red Eminence,” Cardinal Richelieu, began a new attack on the power of the Protestant — Huguenot — nobles, though he left intact the freedom of conscience granted them in the Edict of Nantes.

His son, Louis XIV, whose 72-year rule began in 1643, was another matter. The work of his father and Richelieu had laid the groundwork for destroying feudalism, weakening the nobles and centralizing power. He made the Huguenots’ lives miserable, forbidding everything that was not specifically allowed by the Edict of Nantes. This included closing churches and schools and taking children away from their parents. Finally, he annulled the Edict of Nantes by issuing the 1685 Edict of Fontainebleu. The powerful Louis may have been manipulated into this by underlings. Some have also argued that he was pushed into issuing the Edict by his very religious mistress-to-become wife (who finally became queen through the help of intrigues), Madame de Maintenon. Others say she was opposed.

Julie Philipault. Racine Reading Athalie Before Louis XIV and Madame de Maintenon

Louis XIV continued his father’s work on the Louvre. He ordered the completion of the buildings surrounding the Cour Carrée. In 1661, when a fire damaged the Small Gallery, he renovated the space as a Gallery of Apollo, to honor himself, the Sun King. He then ordered a competition of architects to design the famous Louvre Colonnade, a major example of French classicism.

But Louis moved his court to the more spacious quarters of the new palace he built at Versailles. The Louvre was occupied by the foreign ministry, academies, archives, artists, artisans and courtesans. The Salon of painting and sculpture was held there every two years.

Over the years, there began to be discussions that the Louvre should be a museum. When the Revolution happened, it became clear that the Louvre should be a place for the people. In 1793, the Louvre became “The Central Museum of Arts.” Napoleon Bonaparte had another wing built — on the north side, along the Rue de Rivoli. The Arc du Carrousel was erected in 1806 to the glory of the Grand Army. Then Napoleon III (1852-1870), having torn down much of what was between the museum and the Tuileries Palace, built two more big wings: the Richelieu and the Denon.

In 1871, during the Paris Commune, insurgents burned down the Tuileries Palace.

And then it took another François — François Mitterand — to begin, in 1981, a huge phase of new construction on the Louvre, called the “Grand Louvre” project. The project involved the construction of architect Ming Pei’s pyramid and a 17,000-meter hall underneath it. Mitterand also issued a formal apology for France’s treatment of the Huguenots.

In 2012, in the Cour Visconti, a new space was unveiled, with the formerly open courtyard covered by an undulating glass roof. This space was intended for Islamic art.

Such more modern additions to the Louvre have at times provoked mixed feelings, but eventually have been largely accepted as part of the evolution of the Louvre: from a fortress to keep the English at a distance from a country fraught with religious factionalism, to a home for art — from all religions and the entire world — bidding the whole world welcome.

P. Walton

A great approach to history. Thanks to Apraksin Blues and Ms. Walton.