What Can the Future Be? (Two Shores of a Survey). Continued.

Published in: 26. Non-ReturnThe Editors are inviting authors who contribute to AB as specialists in various disciplines to answer a series of questions about the future of the cultural fields they are professionally associated with. Instead of guessing, we consider it important to learn their opinions directly.

Part of the resulting responses have been selected for publication. In this issue we begin to acquaint readers with these experts’ opinions on the future of culture.

While preparing the magazine for publication, we have moderated discussions among generalist readers about the responses chosen for print, and also offer the most provocative, sometimes potentially controversial, fragments of these discussions for contemplation. Perhaps this will inspire a wish to voice other points of view.

The Editors thank all the specialists who have responded to the invitation to share their thoughts on the future, as well as all readers who have shown themselves far from indifferent to issues obviously critical for everyone.

All translations from Russian (survey questions, Questions from the Audience, Alexander Markovich on the future of science) by James Manteith.

ARTS: MARK BAER

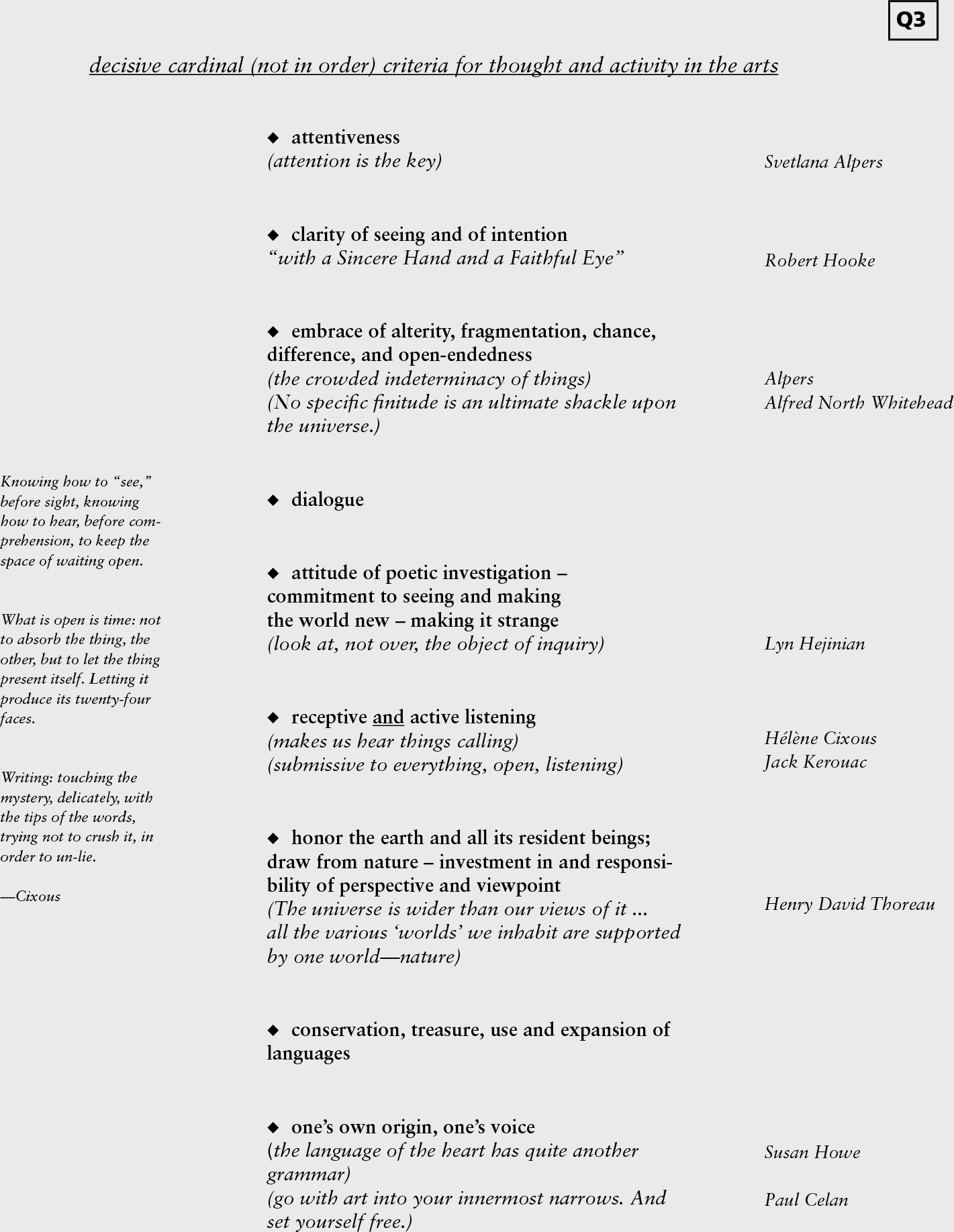

ARTS: GREG DARMS

ARTS: MEREDITH STRICKER

SCIENCE: ALEXANDER MARKOVICH

See also: Part One of the survey responses, from AB 25, “Of all the…”

— ARTS —

There will be more technology involved. This will add a degree of complexity. This complexity will hopefully be tempered by an opposite push towards greater simplicity and clarity of message.

The most central value is the individual artist expressing what is central to their own life – an art that comes not from the intellect but from the soul – a single person discovering a personal insight can be liberating for many – be original. Have something to say and say it. Be true.

Art is not so much about thinking as intuiting – exploring – and then executing in new and exciting ways. Does it rock? Does it shake the roof? Is it wham? Is it bam? Does it frighten? Does it enlighten?

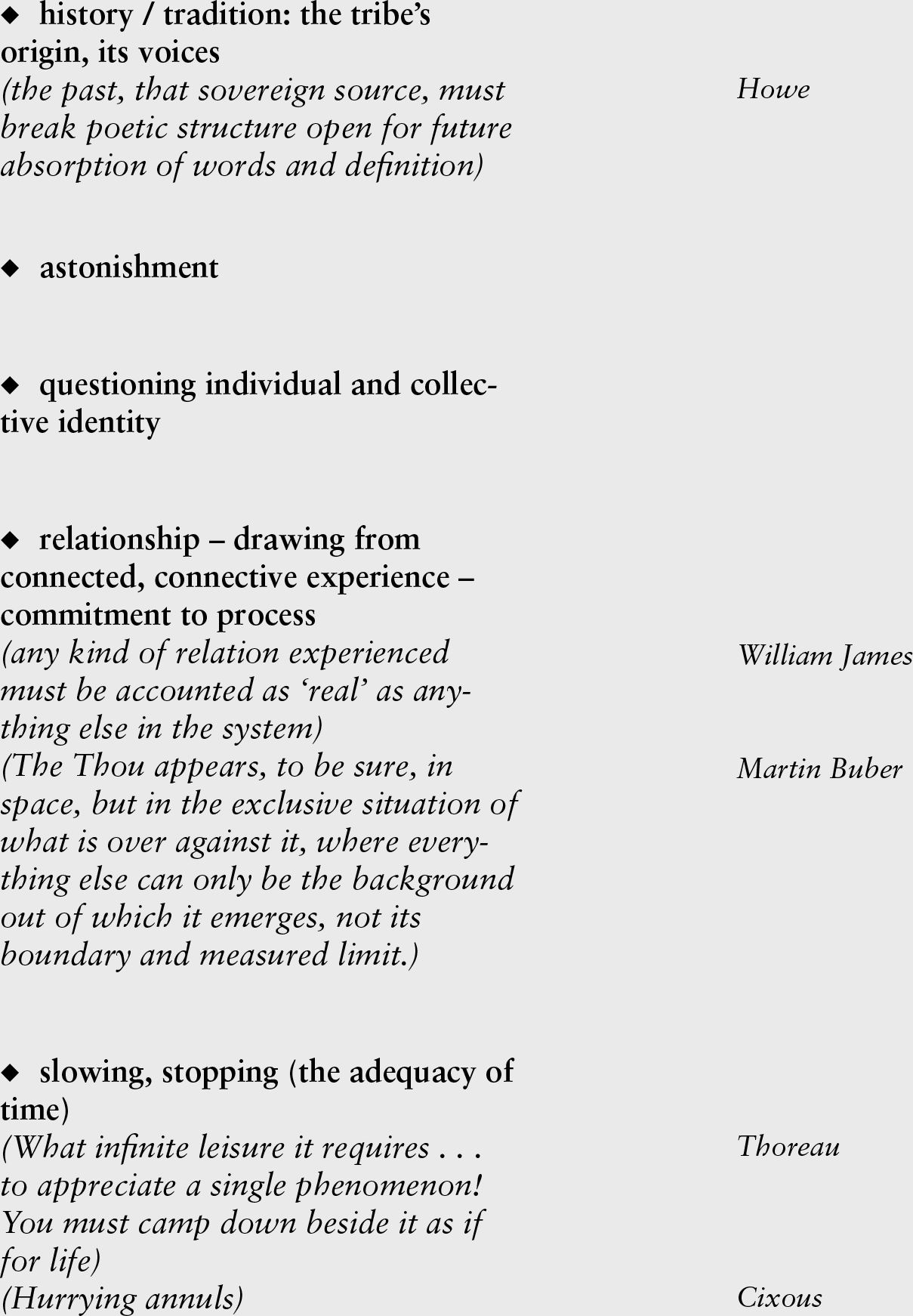

The artist has a tribal duty to beam down the news from the sky and feel the beat coming up through the feet and be fearless and accurate in expressing the message as it filters through their creative prism.

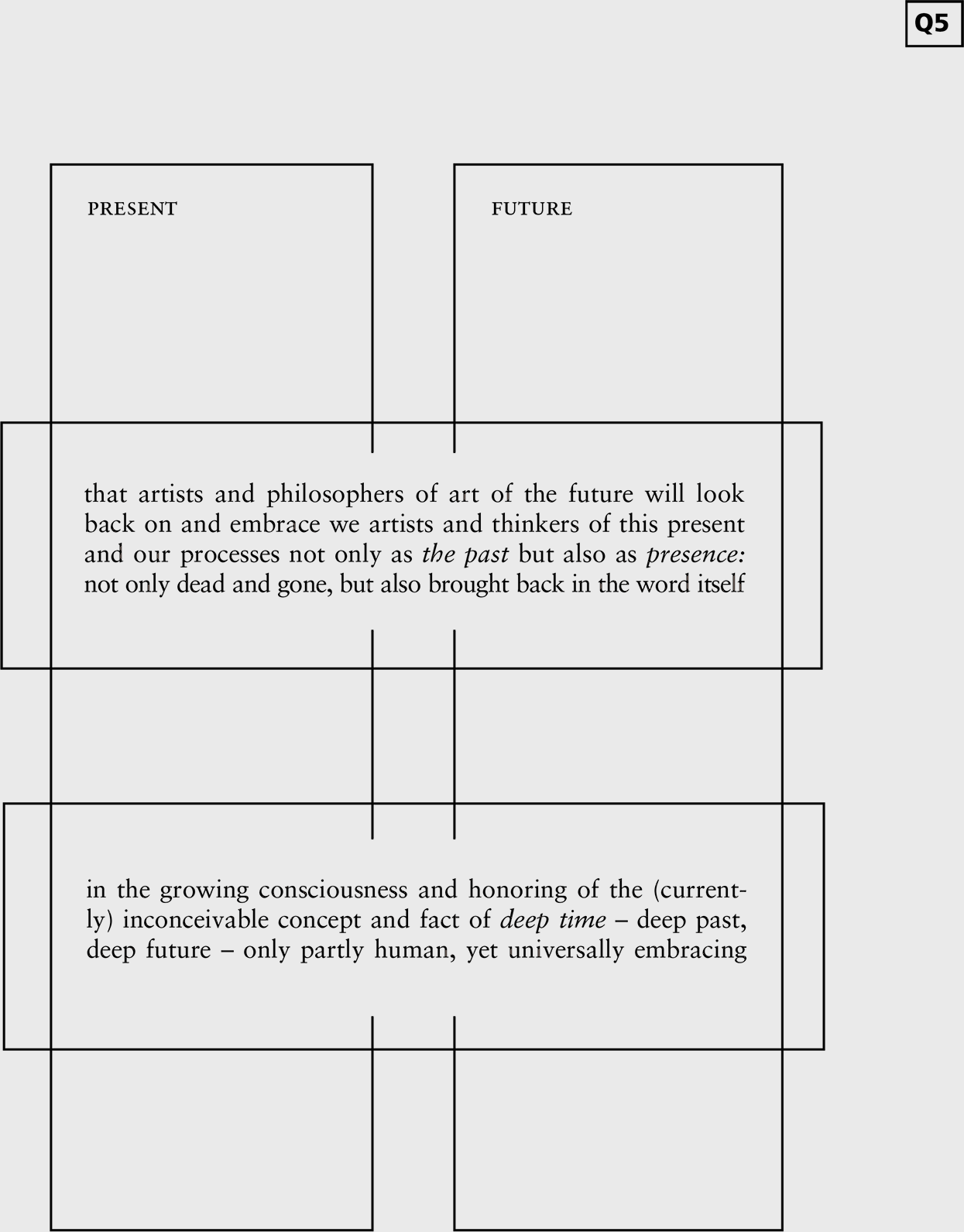

There is great art now – there will be great art to come. Past, present, future, nothing new under the sun – but each generation must express itself in a new way and see the world through fresh eyes…what is always exciting about the future is there will be art not yet imagined…

Everything must go into art – nothing is not important, particularly the trivial. Pragmatically speaking, an artist should know art history and a have a deep cognition about how he/she as an art worker came to the present moment. All artists are part of an evolving story. Art is a language. The more fluent you are the better. Art, for many, is also a religion, a path to the Beloved. And if it is just a job, you better be bloody good, because it is competitive and vicious out there…

Passion, insight, sense of beauty, revolutionary spirit, humor, honesty, integrity, poetry, creativity and work ethic – all important – facility is not so important…too much facility might even be a distraction…

Art is the product and residue of individual artists. Those with indomitable spirits will not be stopped no matter the situation. Art is a sacred calling – nothing will stop a true artist…except mounting debt that impacts the lives of other people – and often not even then…

Yes…but there is no ideal art – only art that is ideal for a particular artist – the perfect mode of expression that best suits what we wish to express like Charlie Chaplin’s baggy suit and hat– sometimes the ideal mode was invented 2000 years ago – sometimes we have to anticipate years into the future….the ideal is a matter of necessity…and remember, nothing goes out of fashion as quickly as the new…and rightly so, the ideal is usually only ideal in the moment – like fresh flowers…

In every way…we will always draw on cave walls with sticks of chalk…

In every form… whatever we do will be contemporary if it is to have the ring of verisimilitude no matter how old the form…ancient ideas are another thing – except to illuminate or contrast the new.

Yes…

No…

Yes…Picasso couldn’t steal if he didn’t know what was going on in his neighborhood…

Seamlessly – art should never be walled off from other modes of thought or expression…the combinations are infinite. Welcome any situation where individuals with different skill sets collaborate on a common problem…

Ideal cultures are only after the fact…

Culture is an embodiment of our highest selves and a mirror held up to our worst tendencies… Culture is our collected wisdom and demons, our poetry and our sins…

From my perspective culture means nothing – I am more interested in couture…however as an artist operating within a culture and a community I feel a compulsion to express what is most personal and psychologically sensitive to an audience outside of myself – I assume my hard truths and insights are not unique or special and will resonate with others – in other words, I am seeking where the “I” meets the “We”…where RADIO ZEITGEIST meets RADIO ME…

– Mark Baer, artist

Director, Museum of Monterey, California

QUESTIONS FROM THE AUDIENCE

— ARTS —

14. How might you picture an ideal culture?

QUESTIONS FROM THE AUDIENCE

— ARTS —

“WHAT YOU DON’T HAVE IN MIND IS A FORM OF DEVOTION”

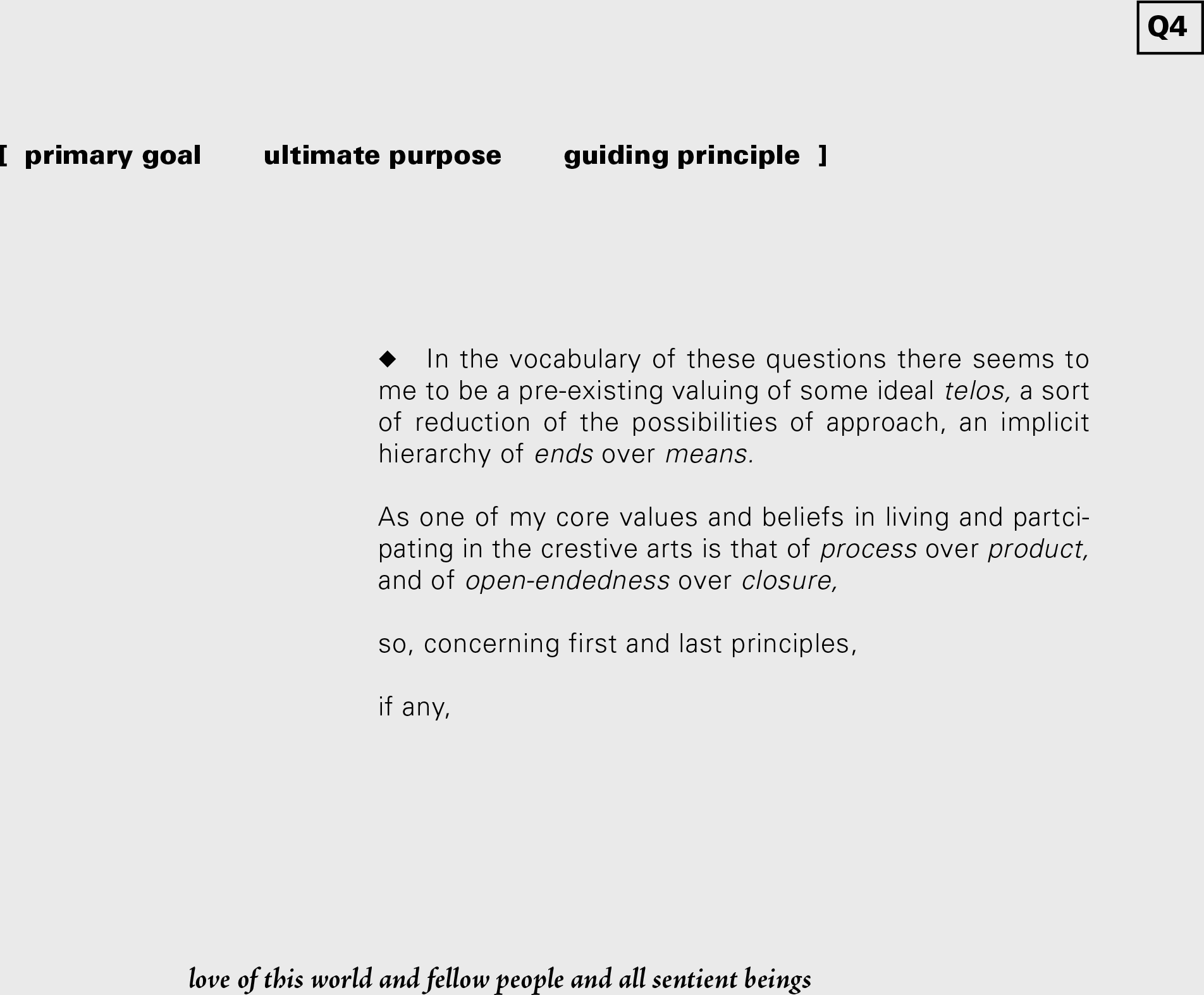

ESSAY ON THE FUTURE or the impossibility of prediction

I cannot even know the future of a current work of art that I’m making, let alone the future of Art in the collective or aggregate sense. Imagine trying to predict the pathways of clouds or the precise shape a burr of metal shaving will take when you pull an etching tool across a zinc plate that catches ink at its throat with an unprogrammed beautiful jagged mark as when Goya invented aquatint for shades of grays to speak for the indiscriminate savagery of his time, clarifying hell as a cloak between himself and his corrupt over-fed patrons who bring to mind a recently sighted license plate on a red expensive car < A · V · A· R· I · C· E which may have been chosen by a snow salesman who avers ice or Ava Rice from Costa Mesa or corrosion spreading from highly unstable compounds such as the aqua fortis at a printmaking institute where I was briefly in charge of the acid baths and when I noticed, driving home, a speck of nitric acid eating its way through my blue jeans –– what you don’t have in mind is a form of devotion.

Somehow, we feel our way into the unknown through the sensitive particles and recombinations of words, for instance: the permutations of flume < blheu < swollen overflow <undulant flux or tree-bark “swelling with growth”, becoming fluent with mistake, a list of one’s own mistakes, as in admitting all of them. There is a future in art that is large enough to encompass “admitting the old excluded orders” [Robert Duncan] compared to “basically we got it about right” [Cheney on the War in Iraq]. John Cage spoke of writing his mesostics and the creative process itself as a kind of unpredictable sensory exploration of unmapped terrain: “it’s as though I’m in a forest hunting for ideas”. We could also call this process or Future of Art a kind of Paradise, with nothing off-shored, othered, otherworld-ed, nothing future-raptured. The future itself is all here, at a continuously unfolding nexus where the unwanted is met with open attentiveness, which is itself a form of love.

How shall we proceed? Cage advises us “to diminish the ego activity that limits the rest of creation.” We’ll take his advice and apply wet tea bags to the page and drive over the page with a car and expose the page to divinatory elements in the backcountry of Pico Blanco and draw in the dark with eyes closed, using small irregular shards of copper, entering the future together in this very moment.

QUESTIONS FROM THE AUDIENCE

— Gary Gumov, Delaware

Speak Your Mind