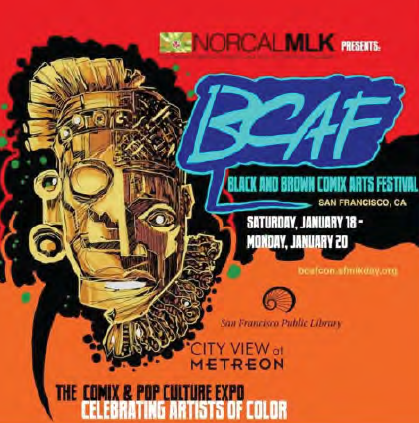

Martin Luther King Jr. Day is observed in the United States on the third Monday in January. The Reverend Dr. King is honored throughout the world, like Gandhi, as a martyr with a message of love and dignity. This time, I have a chance to celebrate in especially good company: David Campbell invites me to meet him at the Black & Brown Comix Arts Festival, held at San Francisco’s Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. A professional designer and a talented musician, David is also a comics artist. His work will be displayed at the festival.

The evening before, I give David a call to confirm — in part out of concern that a recent spell of torrential rains and flooding might impede his drive up to San Francisco. It turns out he’s already in the city, staying overnight and attending, at that moment, a festival event hosted by the Cartoon Art Museum. On that holiday weekend, I’m also not far away, across the bay in Oakland. From the nearest commuter train station in the culturally diverse Latino district of Fruitvale, reaching the festival should take just half an hour.

The next morning finds sunny weather in the Bay Area, and the above-ground, elevated portion of the train route gives clear, freshly rain-washed vistas of life in Oakland’s gray zones: homeless encampments, graffiti-festooned warehouses, personal and commercial traffic crawling along a freeway. After an underground stretch that passes through central Oakland, the views shift to landscapes of similarly motley residential and industrial areas. Port cranes and shipping containers dominate the nearest approach to the bay, while beyond them San Francisco’s skyscrapers loom ever closer. Next comes a plunge into a tube leading across the bottom of the bay. In the tunnel, the train’s noise heightens into a banshee-like wail. Although other passengers seem unperturbed, I can’t relax, thinking about the underworld, seismic faultlines and the weight of water overhead. Then comes my stop at Montgomery Station, I climb a few flights of steps, and suddenly I’m surrounded by office towers on San Francisco’s Market Street. Just a few blocks’ walk away are the glass panels of the Yerba Buena Center.

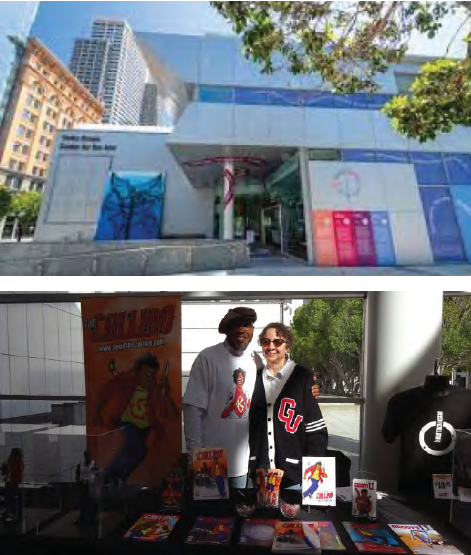

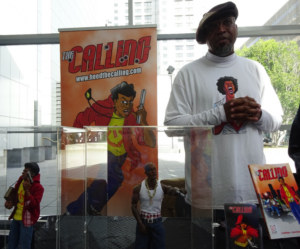

Past a courtyard with postmodern sculpture and a few berths where homeless people rest, I notice a white-bearded man playing African drums beside the entrance to one of the buildings. Indeed, it’s the way to the comics festival, and inside, down a corridor full of artists, is David Campbell, together with a companion in a black-and-white letterman jacket — his wife Camille, a veteran, I learn, of David’s comics conventions.

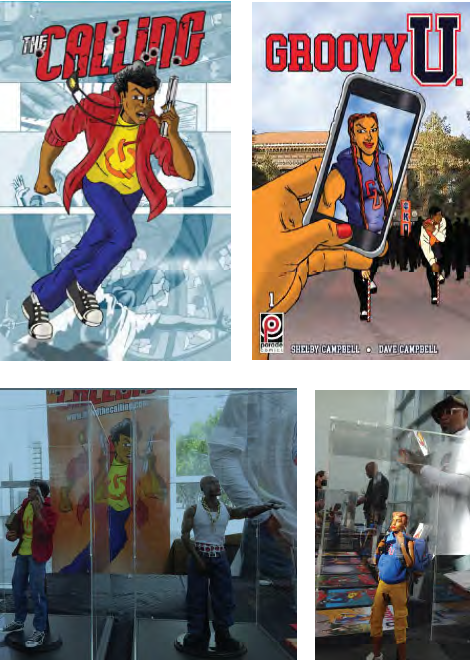

After an exchange of greetings, David gives me a tour of his exhibit. His table holds the first story cycle of his series The Calling, accompanied by a separately bound volume compiling the contents of all five issues, minus the individual covers. Also on hand is Dave Campbell’s Sketchbook, providing glimpses of how the artist develops his characters. What’s more, a new series is also underway, its first issue on display: Groovy U, illustrated by David and written by his daughter Shelby, a graduate of the University of Iowa’s renowned writing program. Now she works in Hollywood. Each title bears the imprint of David’s own independent publishing venture, Parade Comics.

The gritty series’ storylines, David explains, feature characters trying to turn their lives around. In The Calling, a young man getting entangled in a life of crime has an epiphany of faith, which leads to him battling crime instead as an undercover agent. In Groovy U, a young woman starting studies at an all-Black university, Grovingston, is financing her education by working as an assassin. David says she’ll also have a change of heart and try to find redemption. In the first issue, though, it’s still too soon to say how she might break free.

At each end of the table stand display cases containing sizeable action figures, made by David: One case holds hero Silk and villain Bounty from The Calling; the other contains heroine Kacy Spade from Groovy U. The figures delight many visitors, children and adults alike, who pass by David’s table. I realize, too, that the colors and puffy “GU” initials on Camille’s jacket are those of fictional Grovingston. More Calling promotional materials — a large orange silkscreen poster and a torso modeling a black T-shirt declaring “Heed the Calling” — complete the impression of a creative endeavor being realized in many dimensions.

I ask David about the history of Black comics. “When I was growing up,” he says, “whenever a comic book had a Black character, my friends and I would always notice and talk about it together.” As usual in earlier eras of U.S. entertainment, at first some of those characters were sidekicks, part of superhero ensembles or secondary to main plots. That was at first the case, for instance, with Black Panther, who debuted in the 1960s as part of Fantastic Four/Avengers comic books and serendipitously shared a name with the Black empowerment party founded in Oakland around the same time. In the few initial issues with Black Panther that David and his friends collected, the superhero always wore a mask. Was he really Black? When the mask finally came off, they rejoiced, seeing themselves in the character more confidently.

Left to right: Black Panther’s first appearance in Fantastic Four (1966). The early 70s appearance of Luke Cage, AKA Power Man, and the 1977 launch of Black Lightning, DC Comics’ first series headlined by a Black superhero, impacted David deeply, as did the concurrent release of a series devoted entirely to Black Panther. David and his friends also loved the X-Men series, with its Black woman superhero Storm and tales of mutants working to aid the human race.

Now extending Black comics history in his own right, David is dedicating his talents to a good cause and enjoying the growth of his skills along the way: the last Calling issue’s artwork is noticeably stronger than the first’s, as the artist sees it. And comics, as David will always remind us, are also a form of art.

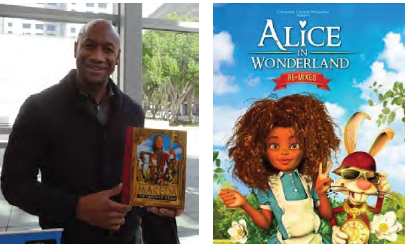

At the table next to David and Camille sits Marlon McKenney, a graduate of the Art Academy of San Francisco across the street. Marlon’s graphic novels imaginatively depict facets of Black history, such as the Queen of Sheba’s ascendancy in the empire of Ethiopia.

Marlon’s Alice in Wonderland Remixed, with Alice transformed into a little Black girl, interweaves depictions of Black leaders as a learning aid for children. The book ends with a “Who’s who” glossary.

Adding to the atmosphere of eclectic solidarity, beside a pair of Latino artists sits a woman dressed like an ancient Egyptian priestess with a crescent moon on her brow. She offers mythologically tinged comic books full of leadership lessons for young girls. Another woman, Lola, who has a shop in nearby Berkeley, sells African jewelry, Nigerian-sewn dashiki dresses and cocoa butter salves. Some of the artists offer comic books expressing a blend of culturally aware mysticism, prophecy and science-fiction known as “Afrofuturism.” The festival also has a place for complementary allies, such as a Buddhist meditation group that views its practice as another means of working for the betterment of humanity.

When I leave, a Calling T-shirt and a couple of books tucked under my arm, I also take along some of the freshness that has filled the whole day.

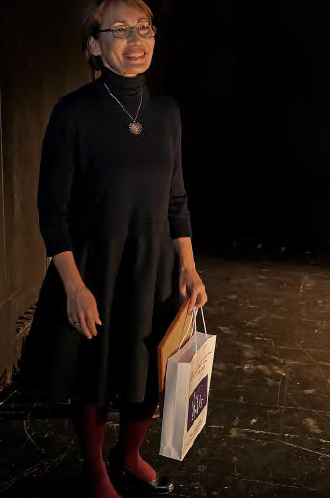

I pass a woman arriving at the Yerba Buena with her young son, hand in hand, and hear her speaking to him about “Dr. King.” Nearby, on Mission Street, a long line of patrons waits for admission to the Museum of the African Diaspora.

Back underground in the Montgomery BART station, I barely miss my train back to Oakland. The next one won’t arrive for at least 15 minutes. I sit down on a round cement island on the platform, open my copy of The Calling and begin to read. Absorbed in the ordeals of David’s characters, I barely notice the time passing.

When my train returns to above-ground Oakland, the day’s plotlines seem sketched across the cityscape, a scene for tales of lives spent in a showdown between good and evil.