“above paint, above colour, above design”

— Emily Carr

Recently I came across an old article of mine about art. More precisely, my very first such article, written in 1991, soon after I first toured the United States as an artist. The piece had gone unpublished — not only due to Russia’s conditions at that moment, but also because I considered it too unpolished. That didn’t keep it from circulating among my acquaintances for a while in a classic samizdat version.

Since then, I have occasionally returned to that first article’s themes, developing and deepening some of them.

Revisiting the article in an already accelerated new millennium, I realized that the piece’s age and imperfections, along with changes in certain details of the context, not only had not dated it but, quite the opposite, had made it even timelier to share openly.

SOMETHING MUCH MORE

At one of my exhibits, at the House of Scholars in St. Petersburg, among an evening discussion’s attendees was an elderly academic. Describing his impressions, he admitted his inability to view my paintings as art. To him, he clarified, they seemed more like research. I felt a bit dismayed by his accentuation of research and painting — that is, art — as opposites: after all, I had always approached them as essentially the same. Indeed: isn’t art in itself already a search, a study? A study, put more finely, of accessing the image of eternity?

Art has no duty to come equipped with knowledge; it functions to connect with knowledge, to trailblaze toward it. Much as a window, not fit with knowledge of what it shows, permits seeing the scenery beyond (unless blocked by shutters of mannerism or intellectual fabrication). Except art, unlike a window, acts selectively, can decide which side or angle to prefer. And a viewer or listener also makes his own choice between the depths of the scenery or the limits of perusing the window itself.

“…doors and windows open there to all the heavens” (H. Hesse on art).

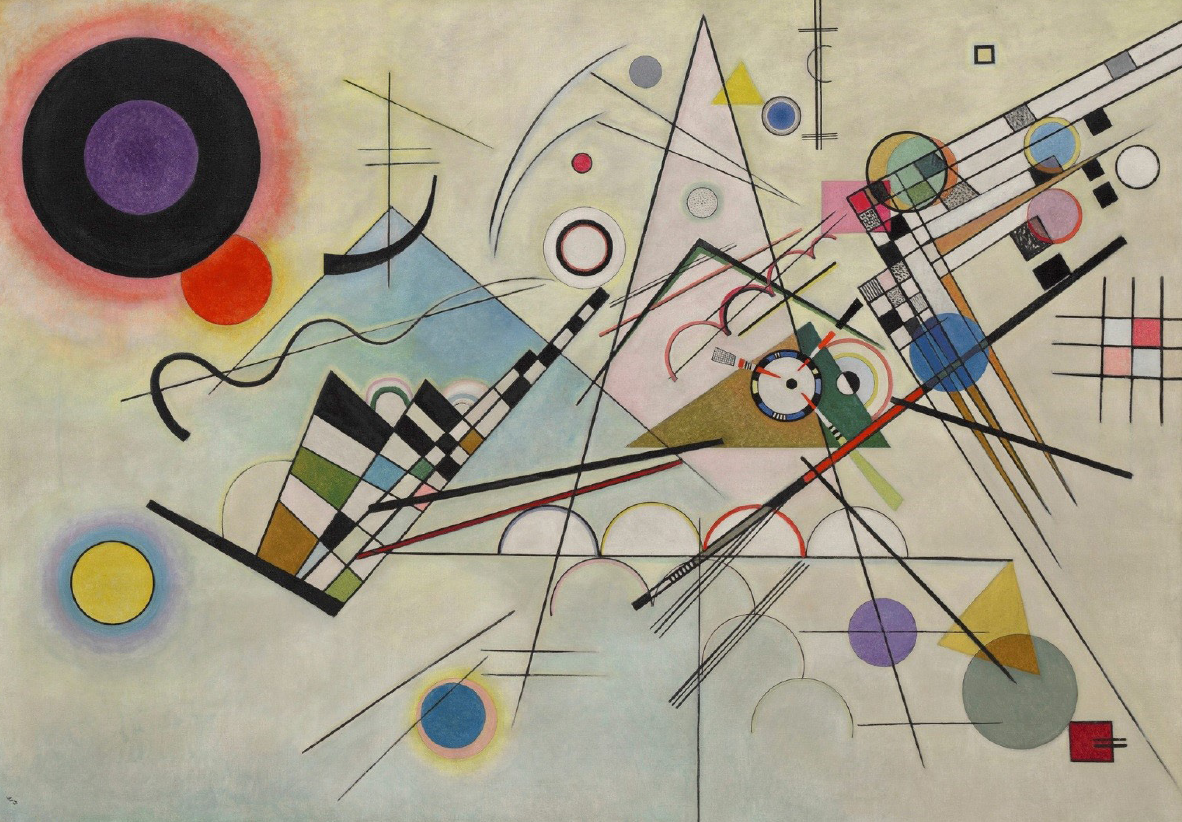

When I speak of art, I speak of music. In general, whatever the subject, for me it is always music. Ranking music beside other arts never seemed fair to me. And not even due to its customary standing as the most exalted art, the most universal, the most intelligible, and so on. I firmly believe it is wrong to categorize music as one of art’s types. Quite the opposite: all art as such is really only just music. Furthermore: art’s other “subtypes,” in my view, are just mimicries of music by extramusical means. Distinct models of producing music without sounds: silent music-making. Goethe’s well-known definition of architecture as “frozen music” could extend to other forms of creativity: the music of gestures, the music of lines, of color, and so on. Familiar? But no, I’m not speaking of expressive rendering but of the musical basis of art’s actual content, the core, the axis that beads creativity. An artist’s forms, media, metaphorical contours and even convictions vary and fluctuate. Yet art’s essence remains changeless.

“We bear all passing things without a murmur, if only the eternal remains present for us at every instant….” (Goethe)

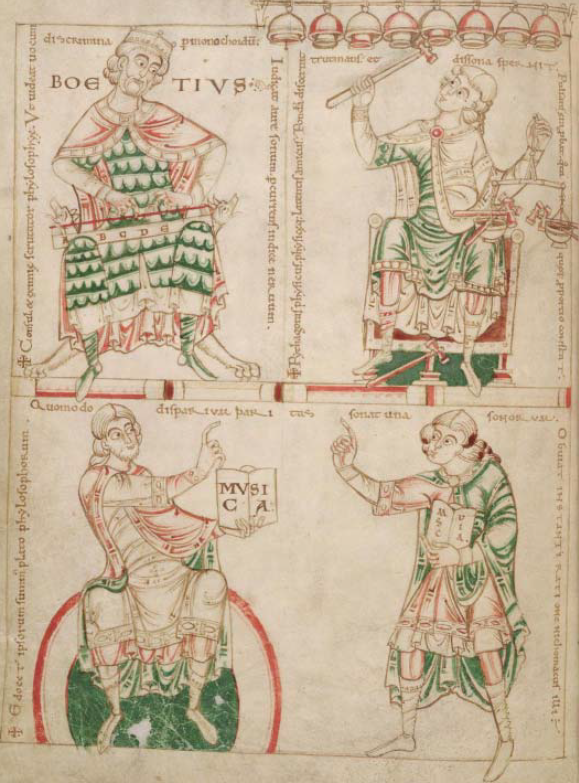

In proposing music as not one of art’s forms but, on the contrary, including them all, I rely not only on my own observations. In fact, this news is rather old. Just check the original meanings in the Latin: “Musica,” says a dictionary, “is the art of the Muses, that is, art in the word’s broadest sense.” The word “music” concerns all the arts, incorporates all nine, the tally of the Muses — among whom, by the way, is Knowledge (returning to the issue of research). And most remarkably, the nine arts, Music’s nine parts, also include the art of music itself. Music emerges as different from the art of music. Music is something much more. At least nine times more.

In aiming for a clearer definition of audible music’s nature, I tend to turn to a basic characteristic: music is never a fully formed substance. This is a known fact. Music is a process. Not fictional, not conditionally stated, but actually occurring. It transpires outside the context of developing situations and scenes meant to provoke a certain reaction or attitude, like what happens on a theater stage. The musical process, discernable in a crafted work or even a separate musical phrase, is itself already that attitude, is a reaction. Namely that makes it exceptional. The musical process demonstrates a developing and active attitude as such in a crafted state, by itself, totally outside any thematic conditions (although the author’s initial impulse probably had its cause). The art closest to this subject-transcending principle is poetry, but it too deals with specific metaphors, with references to definite contextual material. Even the most abstract poetry somehow must make its way to the emotions through imagination, which it guides with causal logic, engaging the awareness with imagery from the material world.

Music draws not on reality’s circumstances but directly and wholly on an intrinsic attitude toward this reality. It does not show a world of phenomena, but iterates a process of their interaction, distilling this into a well-kept order a work expresses — an order enduringly fair, unconditionally and under any conditions, however applied and scaled.

I might define music’s essence, for myself, as a formula for attitudes of interdependency. Ernest Ansermet, the Swiss conductor and music scholar, suggests music’s logarithmic underpinnings: “…the logarithmic basis is not the octave as such, but the octave’s inner ratio between ascending fifth and descending fourth.” In his opinion, this corresponds to the rhythmic structure of the work of the human heart.

Here is Thomas Mann’s more poetic statement: “…music has always seemed to me personally a magic marriage between theology and the so diverting mathematic. Item, she has much of the laboratory and the insistent activity of the alchemists…”

And Igor Stravinsky’s voice adds, “The phenomenon of music was given to us solely to establish an order in everything that exists….”

In one of ancient China’s earliest known texts, we find this assertion: “The governing of a kingdom is like music.”

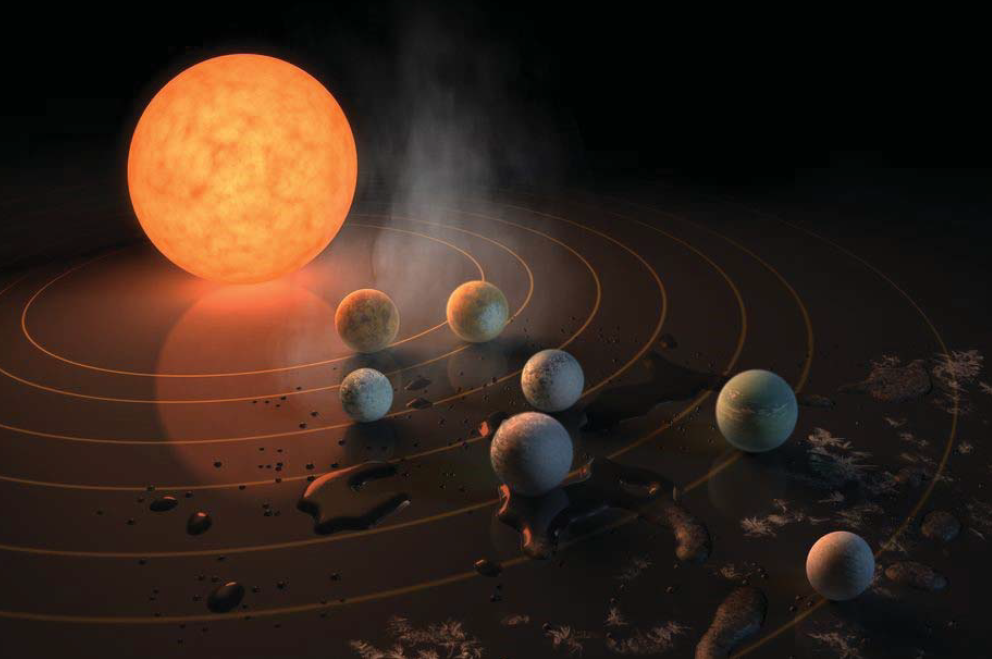

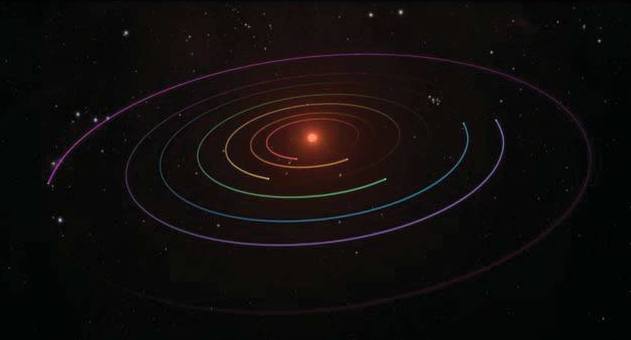

Music truly can govern, and it can govern not only a kingdom. Much like a family’s diminutive copy of a unit of state, a state itself is simply a single model of infinite concentric cosmic spheres where the actors are no longer humans or terrestrial nations but planets, constellations, whole galaxies. The ancient Chinese canonical sources attest to music controlling the movement of planets, each planet correlating with a certain note (and tonality). Music’s cosmic influence emanates in principles of earthly life. These principles are supposed proper to know and follow: “music opens the way for winds from mountains and rivers”; the system of measures of length and weight accords with laws of music; musical harmony’s disposition in nature determines timings for agricultural labor. In political prognostication, musicians ranked alongside astrologers in wielding preeminent authority. (Compare this with the words of Matheson, a contemporary of Handel: “Once musicians were poets and prophets.”)

(The Pythagoreans held a “theory that the heavenly bodies’ movement produces a harmony, because they make sounds that combine in consonant intervals,” as Aristotle reports in “On the Heavens.” Ansermet’s account of a logarithmic musical principle aligns with the Pythagorean view: “Starting from…the observation that the stars’ speeds, as measured by their distances, are in the same ratios as musical concordances,” Aristotle continues, “they assert that the sound produced by stars’ circular movement forms a harmony.”)

In Ancient China, here is how life was ordered on music’s basis: “Divine musicians of antiquity explored the middle sound and measured it to develop a system of music. Based on the middle sound, they set the length of the pitch pipes for the remaining notes, and determined the size of the pipe to produce the middle sound. All officials have taken this as an example in matters of government.“

Also, the size of the same musical pipes formed the basis of China’s system of measures.

So just what is music? Posing that question, I propose this answer: music is a manifest, universal principle of the process of living.

Another musical phenomenon to mention is the perception of music — unlike other things (unlike all other things) — occurring not as a dialog, with information synthesized before a reaction forms, but as a monolog merging subject and object in unity. Listening to music always means living it from within, inside, from the flow of your own individual feelings: not as a reflection of your personal destiny, not as a description, not as a semblance — but as living through your own segment of life. Music is the voice of my own heart, the heart of its listener. If all art as a whole may symbolically resemble an icon, which gives an image through which contact with the Absolute occurs, then music itself is an appeal; with music itself we turn to address the highest. It becomes a personal, individual path to transcendent spheres, becomes one’s own word born in the soul. This is one of music’s most striking properties, and I think seeking analogies leads nowhere. Music comes from without, yet is lived as one’s own experience.

In describing a musical impression, a person speaks exclusively of his own sensations: of love, anguish, triumph, danger… Yet in fact these feelings had no cause other than music.

“I had a feeling as if eternal harmony were conversing with itself, as might have happened in God’s bosom shortly before the creation of the world.” (Goethe).

Could it be that namely in this aspect, of being experienced as an event internal to the soul, lies the secret of the baffling power of music? It becomes part of a person’s biography, a step in the development of spirit.

“The musical impression becomes real,” it is “like experiencing truth.” (E. Ansermet).

Some maintain that neither art nor music can be divided into light and serious works: art is either good or bad. What does “bad art” mean? Bad, but still art? Or, if bad, maybe it isn’t art at all?

An American composer in New York took me to a museum known for its large collection of pop art. As we roamed the spacious, deserted halls, he remarked, “I never could understand why things get called ‘art’ that have nothing to do with it.”

Etymologically, the word “art” indicates foremost an element of outstanding mastery, perfected craftsmanship. The “art of the Muses” presupposes creative mastery, that is, a high degree of professionalism in embodied creative tasks. Activity moved by spiritual need and based on finely honed craft.

Whatever might be called art in our day (and usually now everything is, and rejecting anything seems awkward), everyone still knows the difference between a skillfully prepared lunch (an example of “culinary art”; incidentally, P.I. Tchaikovsky grouped certain compositional productions in this category, calling their authors “musical cooks”) and a great masterpiece by a spirited genius. The former is for the body, the latter for the soul. The former could be said to serve the latter (or ought to do so). Aesthetics act as a layer for their mediation, conveying the subject the most perceptually optimal “design.” Namely this borderline “aesthetic” territory sees shifting and swirling notions of what is art, what is craft, what is self-expression, what is self-infatuation and what is infatuation with truth. Age-old boundaries — not only between genres, but between ends and intentions — seem stripped of their outlines and tramped down into a smooth surface where bewildered concepts scurry, totally losing their dignity and opting to seek happiness as each others’ guests, with other masters, in another country.

In this kind of mixing of levels, the overall result declines markedly — a predictable pattern in any such situation. Although what we call “high art” made assorted gains with equality achieved, this only came about at the extremely steep price of opening its territories to huge numbers of foreigners. That then drastically affected its own standard of living and creativity, while leaving the newcomers’ issues unsolved.

This results in our obtaining the blatantly average: mass culture. Democratic accessibility is synonymous with democratic prowess, which seizes hold of ever-greater expanses formerly viewed as the property of spiritual and intellectual refinement. Non-participation in this shift of power is roundly condemned and dismissed — what use does free modern society have for old-regime egoistic elitism?

Such a situation might well seem justified, almost ideal: art looks accessible to everyone, creativity no longer exists as a realm for the elect. We conscientiously learn to esteem expressiveness and exquisite originality in things absolutely not meant to contain them. This might not only seem but could also be ideal, if the middle, the general level where creative (both “creativity” and creativeness) activity has its maximum intensity, were calibrated right. By the way, the law of the golden mean situates the optical midpoint between upper and lower parts, the point of their equilibrium, slightly higher than the geometric center. And not only in our perception. To avoid downward gravity, the average should surpass the democratic middle.

Becoming democratic, art mounts a marketplace foundation. Judging creativity by monetary units is a kind of human trafficking. Speedily enslaved by consumer ideology, art formulates all its pros and cons according to, influenced by, the character of demand. “To each according to his labor” is developed society’s law of economic relations. Perfect! Especially if you have criteria for gauging effectiveness of an artist’s labor. Why is he needed at all, what can he offer that anyone would lack without him, that people can’t provide for themselves, given access to high-tech industrial infrastructure? And so the artist submissively obeys, reborn as a manufacturer: art also becomes an industry, an industrial sector, yet one powerless to make something not already made by other industries, something of exceptional merit and value — after all, art has fully paid for its modernization: the cost was its self-respect, was respect for creativity. Art now has nothing left but mere lackeydom, answering the whims of a taskmaster in no mood, for his own money, to probe souls’ moral subtleties — even as a decorative element this figures as a distraction, a kind of archaism, much like that once-esteemed mark of true artists, their “honest and so rare seriousness” (Goethe).

An episode comes to mind, a nice caricature symbolic of shaping an artistic psyche as a standard-setting tool for creative mediocrity.

As luck would have it, in San Francisco, in one of the Institute of Arts painting studios, I observed a young student in the throes of work. Setting up, then facing, a sizable canvas, the youth passionately plastered it with gaudy splotches, flinging paint upon it from a palette — another stretched canvas, just as big, lying horizontally. When a professor and I approached, the student proudly displayed his achievement: his ingenuity had doubled the efficiency factor, and the result raised no doubts. Instead of a single masterpiece, he now had two at once. The student’s shrewdness proved much to the professor’s liking. The progressive method’s author glowed with infantile-imbecile pleasure. It was easy to picture him as a baby with a bowl of oatmeal, finger-smearing around the edges — maybe the first display of his creative ability!

It’s hard to shake off a feeling of busily playing ourselves for fools. The whole thing smacks of pricey psychiatric clinics for capricious patients.

Society shows a penchant for rewarding artistic originality and desires as many extremes from it as possible. After all, it has too little of that, and expects that from an artist, who lends variety to life’s routine background, injecting bright, invigorating hues, offbeat and unique, with his presence, in complementary contrast to the tactical drabness of workaday (or non-workaday), monotonous, ordinary life. The more acutely and flagrantly original, the better — in fact, that yields a necessary tonic effect, which the consumer counts on. Syrup or acid — that matters little, if only the dose stuns the senses. Success peaks at a dangerous brink of tyranny and pathology. And it makes no difference what serves as the vehicle of expression, what means the artist uses to subsidize his inventiveness: the main thing is an undwindling flow of stimulating production. The social stratum still keeps tabs on the artist’s standards: he prefabricates society’s manners, he plies the extraordinary: preferably based on his own appearance, lifestyle and proclaimed slogans. Through this, plain persons more easily believe in their own expert authority and learn artsiness, with the artist left to leverage new extremes.

Herein, too, a cause might well be sought for a catastrophic fall in popularity of the arts’ performance portion.[1] If something’s performed, it should at least be completely unpredictable, rendered unpredictably: otherwise, where to beget originality? Music schools’ performance faculties are rapidly losing prestige. Instrumentalists prefer to “go to the composers,” an easier path to “self-expression.” Composition departments have gotten overbooked. The situation sometimes grows absurd. The aforementioned composer from New York lamented that far from all of his department’s aspiring students were capable of independently playing even half-baked versions of their own compositions. On the other hand, he said, the same university — one of the country’s most prestigious for music disciplines — was down to no more than two cellists, for instance, across all its courses. The rest had retrained as composers and conductors. “Who will play what these young people write?” he exclaimed. “Before long there won’t be musicians left to play even the classics!”

I prefer to keep believing in the classics’ timeless relevance. Including for their performers — for musicians, who have stayed quite numerous enough, in spite of it all. But this discussion extends far beyond the mere fact of a sudden epidemic reluctance to accept the rigors of honest performance — realization — at minimum, of someone else’s music. Much more important is a lack of understanding that creativity as a whole, as a principle, is nothing else but a form of performance!

We somehow like to see the degree of the differentiation, the exclusivity of humanity’s subject, its unit, as creativity’s main measure. Self placing self as the center of interest and giving namely itself expression. (Preferably overwrought, and best when agreeing least with habit.)

If this stance is accepted as a given, then the level of creativity, the degree of its expressiveness and perfection, of course, must depend entirely on individual qualities of an author’s personality. So that’s why developing creative abilities presumes foremost developing self-awareness, personality — depth, insight, receptivity — by cultivating moral capacities. Creating a quality foundation for the personality constitutes the predominant, the most significant part of the whole creative endeavor. This lets the author’s individuality evolve, preserving its core stability, which ensures its personally distinctive emergence — so personally, in this case, that no influences or changes can reduce the value of its idiosyncrasy and matchless originality.

Yet cultivating the soul takes serious, often strenuous work. Recognition, reward for artistic bravery can be earned by a much faster and safer route: not by improving the personality but, on the contrary, by nurturing its weaknesses (and even more preferably, its flaws), inflating them to a scale of distinction, sometimes plausibly pathological. (Tolstoy described this as a kind of insanity, considering it a “final stage of egoism”).

So we find ourselves at the very point that sets a “middle level” falling short of the golden section.

And in this, of course, the public plays the role of a major accomplice, expecting art to provide entertainment, pleasure, domestic decor, exercise for mental agility, relaxation, flavoring for the commonplace — but not art itself, that truth engendering creative comprehension, art’s golden grain, its motor: truth, for whose road art raises the crossbar. More often the notion of truth in and related to art is displaced by craft-backed pseudo-truth, by a generic equivalent of a meal kit — a ready-made recipe, so to speak, to answer an eternal question. Yet art is not an answer to a question, but only a “door leading into the ‘other world'” (G. Mahler).

As Igor Stravinsky writes, “Most people like music because it gives them certain emotions, such as joy, grief, sadness, an image of nature, a subject for daydreams, or — still better — oblivion from ‘everyday life.’ They want a drug — ‘dope.'”

“Music would be not be worth much if it were reduced to such an end,” he then exclaims.

Elsewhere he says the “reveries induced by the lullaby of sounds… [are] what they prefer to the music itself.”

Yet even if not everyone rushes to enter the doors art opens, that hardly means these doors need barring. Sooner or later, someone in need will cross the threshold.

“Open this door where I’m knocking in tears.” Apollinaire, to whom those words belong, is not alone in his call, its tones clearly born of something other than aiming for pleasure or, moreover, entertainment. They pertain to longing for life — the sharpest vital need, the main requirement of a soul. Filling this hunger takes something more than the quirks of anyone’s art as “self-expression.”

“The purpose and ultimate goal of the General-Bass, like any other music, can be nothing else but honoring the Lord and satisfying the soul.” (J.S. Bach).

Following the Leipzig cantor’s example, we can utilize his formula’s universals to assert that, just as art is neither high nor low, it is also neither good nor bad; there is simply art, that is, what meets art’s purpose, and then there is whatever does not meet this purpose and therefore is not art. To restate the obvious: art’s task amounts to “satisfying the soul” and not to irritating primary instincts. All that we call emotions, passion, mood, can accompany art, enhance its impact, heighten its expressiveness, but should not displace its goals. Remember: “Music would be not be worth much if it were reduced to such an end.”

Yet there are endless varieties of styles and genres, limitless ranges of character and means of expression: they enable addressing the same truth at different levels, and in each case in an individual language.

“A song can be as much a work of art as a grand opera finale, if the song has genuine inspiration.” (G. Verdi).

At a gathering which happened to bring together a group of all ages, from high-schoolers to retirees, in the course of conversation a dispute arose: what should be considered virtues or vices in art? What does each person find good or bad, what does each person need or not find needed? And really, how to know? The older people attacked rock music: the younger ones fiercely bristled in its defense. On the other hand, when someone praised the artist Shishkin, the younger people sniffed disdainfully and declared his paintings no better than blown-up photographs.

I think it bears remembering that art is a search for truth, an “artistically embodied truth of things” (P. Florensky). The degree of this search’s success is the sole criterion that determines belonging to art. Truth, like water, is always one. Each person may decide whether to drink it from a glass, or a puddle, a stream or from a teapot after thorough boiling. “There are no paintings that do not serve to correct morals,” asserted sixth-century Chinese painter Xie He.

The renowned pianist Arthur Schnabel relates, “I can enjoy walking along Fifth Avenue and looking at the window displays. I may be perfectly happy. I can also be perfectly happy after climbing for hours to arrive at the peak of a mountain. Only those who have derived happiness from both, the climbing and that strolling, know that they are incommensurable and will, asked to choose, certainly decide for the mountain.”

Not all works of art are equally perfect, not all are impeccable. Their distinctions span not only genre and style, not only eras’ attributes and technical elements, but also the author’s personal inclinations, the traits of his individuality. The scope of the creatively possible is prescribed by the bounds of his own development. “Only a person who improves his awareness and will can express sublime moral principles and purity of spirit,” says another Chinese classic.

“If you would create something, you must be something.” (Goethe).

Everything said here leads up to the theme of music’s religiosity. In this case, I do not mean adherence to any religious dogma (a separate area of consideration). In reality and art, the eternal essence emerges in endlessly plural expressions. Tradition, images from life environs, personal experience, historical events are all materials elevated by the artist’s creative objectivity to a general degree of evidence. An artist is namely an artist in that he always speaks of himself and of eternity. Professed atheist Dmitry Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 12, “The Year 1917,” dedicated to V.I. Lenin, is no less religious than church hymns. In its own language it tells me exactly the same thing as David’s psalms or Bach’s Mass in B-Minor. Thomas Mann writes of music as divine worship with no ceremony.

“The beauty of the body is the soul.” This observation belongs to Leo Tolstoy, but the thought it contains is not his personal hypothesis — its basic axiom has found reflection many times over the course of human history. I recall Chuang Tzu’s description — heard in turn from Confucius — of an occurrence in Ancient China. In the provinces as an ambassador, Confucius witnessed a rustic scene: several piglets gathered around their dead mother and trying to suck her milk. Realizing she was dead, the piglets left her side and ran away. “What they loved in their mother,” Confucius explains, “was not her body, but what made her body alive.”

The beauty of art, its meaning, its content, the cause and justification for its existence is the soul. However perfect art’s body may be — however mathematically irreproachable or sophisticated — if devoid of life, it is at best a corpse. What I would call art’s soul is an authenticity of faith active within it. This is the quality that often makes crudely wrought primitive art so deeply compelling.

However, the popular idea of return to childlike naivety, ignorance, simple-minded purity, by no means settles the issue of saving the soul of an artist. Unartificed, unaffected innocence can be an enticing, charming asset, and yet it presumes itself free of responsibility — and that is the very condition that defines a professional. Primitivism’s appeal stems largely from lack of responsibility, which absolves the viewer of responsibility as well: we too have childlike innocence, though we grew up long ago. Yet mature human awareness necessitates, like it or not, a highly developed sense of duty.

Not accidentally, the word most often associated with making art and living in art is “service,” implying abnegation, relinquishing self-interest, as the self in this case acts only as a servant — a servant of a goal superior to itself, a servant of its higher nature, of a higher principle: to this go the artist’s best energies, labor and perfected mastery. Art’s service and religion’s service derive from the same nature. They have the same object of worship, varying only in range of means and methods. Practitioners from vastly different eras and peoples voice a strikingly unanimous attitude toward creativity as service and self-renunciation.

“…an artist is the apostle of some Truth, the organ of the Almighty, who makes use of him.” (Balzac).

“… I am but a pen so as somehow to write four notes.” (G. Verdi).

“You are a serf to the Lyre.” (M. Tsvetaeva).

“…man…appears to himself like an inspired mouthpiece…” (T. Mann).

“… through our hearts the gods speak…” (Goethe).

Salvation — for an artist and art — lies not in return to the sinless state of childhood, but in ascent to a new stage of awareness — service — “to deliverance: that is, not back again behind morality and culture into a child’s paradise but over and beyond these into the ability to live by the strength of one’s faith” (H. Hesse). Only the responsibility arising after a followed path of knowledge opens the chance of gaining a “new, higher form of irresponsibility or, to put it briefly, faith” (Hesse).

And only this gives rise to art’s miracle and magic, its inexplicable power. Born of faith, becoming faith by means of a conversion.

March 1991

Selected Bibliography

Except as noted, quotations not from English have been newly translated from the source language.

Herman Hesse. “Joseph Knecht to Carlo Ferromonte.” “A Bit of Theology.” (trans. Denver Lindley in My Belief: Essays on Life and Art. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974.)

J.W. Goethe. Letters. Iphigenia in Tauris.

Ernest Ansermet. Conversations about Music (Entretiens sur la musique, éd. J.-C. Piguet. First French edition Neuchâtel: La Baconnière, 1963). Writings about Music. (Écrits sur la musique, éd. J.-C. Piguet. First French edition Neuchâtel: La Baconnière, 1971).

Thomas Mann. Doctor Faustus. (trans. H.T. Lowe-Porter. First English edition New York: Knopf, 1948.)

Igor Stravinsky. An Autobiography (Chronicle of My Life). New York: Simon and Schuster, 1936.

Guoyu (Discourses of the States).

Aristotle. On the Heavens.

Piotr Tchaikowsky. Letters.

Leo Tolstoy. Letters.

Gustav Mahler. Letters.

Guillaume Apollonaire. “The Voyager.”

J.S. Bach. Rules and Principles for the four-part playing of the General-Bass for his musical scholars.

Giuseppe Verdi. Letters.

Pavel Florensky. Ikonostasis.

Zhang Yanyuan. Notes on Famous Paintings of Past Dynasties.

Xie He. Record of the Classification of Old Painters.

Artur Schnabel. My Life and Music. New York: St Martin’s Press, 1963

Сhuang Tzu. The Inner Chapters.

Honore de Balzac. “Artists.”

Marina Tsvetaeva. Letters.

[1] A view of the state of affairs as of early 1990.