On April 15, 1862, Thomas Wentworth Higginson received a letter from a beginning poetess with four poems and two questions: “… say if my Verse is alive? … Should you think it breathed- “… We know the answer of whether her poems are alive, whether they breathe. A century and a half later, her poems still live, breathe deeply, and remain invariably attractive to readers. Poetry lovers need no reminder of who Emily Dickinson is.

Emily’s poems have been the subject of numerous translations. Among professional poets and translators working in Russian, first of all, Vera Markova, Arkady Gavrilov and Grigory Kruzhkov should be mentioned. Besides recognized professionals, many philologists, amateur poets and eager readers have attempted Russian versions of her poetry. But what is the reason for her poetry’s sorcery-like appeal?

For me, an average reader, her poems pose an intellectual challenge. Seemingly, studying dictionaries, it’s possible to define a set of meanings for each word she uses. It is possible to reproduce the most probable equivalents of her grammatical constructions — but never reach the essence, never understand why and what these verses are about. You can review dozens of existing translations and affirm that many translators have taken a formal path of maximally preserving vocabulary and poetic devices, without understanding the hidden meaning, just as I, too, might fail to understand. Emily herself describes this situation with an amazing, masterful accuracy (1101): “Between the form of Life and Life / The difference is as big / As Liquor at the Lip between / And Liquor in the Jug.” Behind an apparently unpretentious form lurks a magical drink of true essence, but how to open the vessel? Grigory Kruzhkov writes, “A translator doesn’t proceed based on words, but based on what Mandelstam called a ‘sounding cast of form.’ The translator’s task is to knead the clay of the poem so long that it becomes soft and pliable. And, from this clay, to mold a new poem.” That advice is good, but Emily is against similar methods being applied to her: (861) “… Sceptic Thomas! / Now, do you doubt that your Bird was true?”

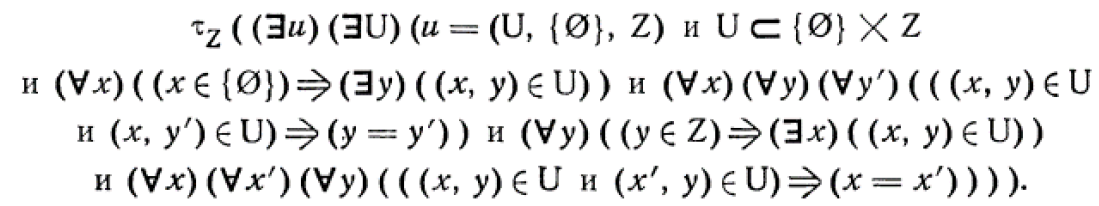

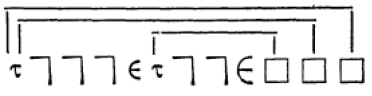

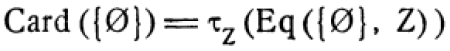

Roman Jakobson in his article “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation” points out, “The pun, or to use a more erudite, and perhaps more precise term — paronomasia, reigns over poetic art, and whether its rule is absolute or limited, poetry by definition is untranslatable.” To agree that Emily’s poems will remain a pun for the Russian-speaking reader, an untranslatable pun, is categorically impossible. But Jakobson suggests a way out of this paradoxical situation. A translation of Emily’s poems should not be a translation, that is, an interpretation of verbal signs through another language, but an inter-semiotic transmutation. With this approach, the act of translation becomes an alchemical transformation. Direct: text to image to thought form to symbol. And in reverse: symbol to thought form to image to text.

About how this can happen in practice, Carl Jung writes, in his “On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry”: “While his conscious mind stands amazed and empty before this phenomenon, he is overwhelmed by a flood of thoughts and images which he never intended to create and which his own will could never have brought into being. Yet in spite of himself he is forced to admit that it is his own self speaking, his own inner nature revealing itself and uttering things which he could never have entrusted to his tongue. He can only obey the apparently alien impulse within him and follow where it leads, sensing that his work is greater than himself, and wields a power which is not his and which he cannot command.”

But it is well known that a philosopher’s stone is required for alchemical transmutation. And that philosopher’s stone is love. Arkady Gavrilov in a diary entry (11/12/1985) writes: “Translation by calculation cannot be happy (unlike marriage, where love can come with time). Only by love!” Grigory Kruzhkov in the essay “Translation and Eros” writes, “What is the reason (raison d’etre) for translations? “The same as in love: attraction to the beautiful.”

In presenting examples of my poetic translations to readers, I would like to conclude with the words of one of Emily Dickinson’s translators, Tamara Stamova: “She is a mystery and a secret, and we admire her because we will never solve it. She left us the joy of guessing and agonizing — of translating!”

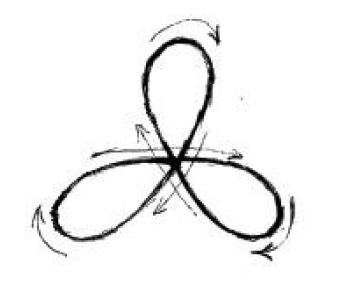

![Way to the Absolute [and from the Absolute]. Mikhail Shapiro. 2003.](https://www.apraksinblues.com/wp-content/uploads/img_5dcd45ae7c2e3.png)

.

. ,

,